News from Maison de la Gare

An Evening with Talibé Children for whom Things Just Got Even Worse

Tweeter

Sonia LeRoy and Rowan Hughes share an extraordinary experience

I have had the good fortune to travel

to Senegal on many occasions to support the work of Maison de la Gare in aid of talibé

street children. My teenage daughter, Rowan, has accompanied me in this work three

times, becoming personally committed to the cause of ending forced begging and

supporting Maison de la Gare in bringing hope to the talibés of Saint Louis. On a

previous visit, we accompanied Issa Kouyaté on one of his regular midnight "Rondes

de nuit" in search of runaway talibé children. And, on our most recent visit, we

spent an evening with the runaway boys currently in the care of Maison de la Gare.

Rowan writes: "I volunteered for the first time with Maison de la Gare in 2012.

I had an amazing experience delivering books, organizing the library, and setting up

e-mail accounts for some of the talibé children. It wasn't until my second trip that

I went out onto the streets and into some daaras. I was shocked and very emotional

at the conditions I saw in the daaras where my friends had to live. But the most

powerful part for me was going out on what are called night rounds.

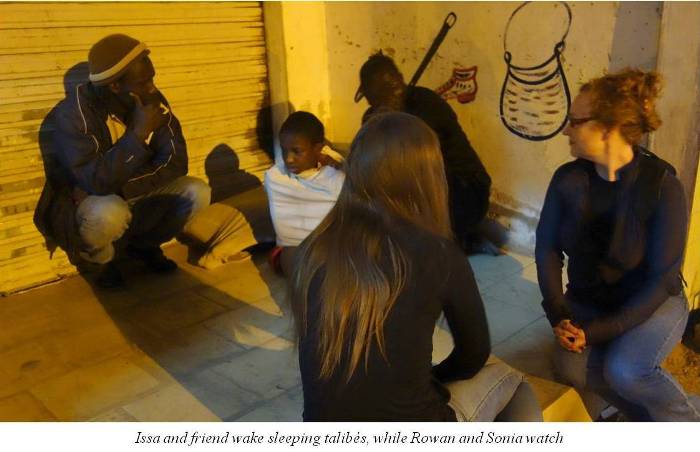

On night rounds Issa, and in this case me, my mother, my grandfather and a man who

helps Issa find runaways, went out in search of talibé boys who have left their

daaras and are living on the streets. Issa talks with them and convinces them to

go back to his home where they can stay until authorities give the go-ahead for

Maison de la Gare to take them back to their villages or, in some cases, return them

to their daaras. We headed out at one in the morning when it was pitch black.

take them back to their villages or, in some cases, return them

to their daaras. We headed out at one in the morning when it was pitch black.

The usually chaotic streets of Saint Louis were dead quiet, and after a day of about

35 degrees (95 F), it was suddenly cold. We met Issa and then took a taxi to a

place where an informant had told him that there may be kids sleeping. The first

place we checked was a parking lot for buses and taxis. It was explained to me that

runaways will often sleep under cars to stay hidden from pedophiles or others who

could hurt them.

We were leaving the lot and heading back into the streets when we saw them. Four

young boys in a lighted corner huddled together. They used their tee-shirts to

cover their whole bodies by pulling them over their heads and tucking in arms,

legs and feet. Issa gently woke them one by one, talking to them in Wolof, and

convinced them to come with us. I couldn't help but wonder what they might be

thinking. Imagine some strangers waking you up in the middle of the night and

asking you to go with them. Issa pointed out that one of the little boys named

Gora had likely been sexually assaulted. He couldn't have been older than 7.

My heart almost broke. There he was shivering in the corner, looking at me.

I wasn't sure what to do; all I wanted to do was give him a hug and tell him

everything would be okay. But of course I can't speak Wolof, so I gave him

my sweater.

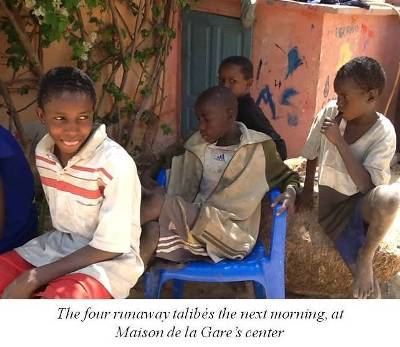

We took the four boys back to Issa's apartment in taxis and got them settled

down with blankets. The next morning we went to the centre and the boys from

the night before were there. Despite the heat, I saw Gora was still wearing

my sweater, and I swear I saw him smile at me just once."

The next morning we went to the centre and the boys from

the night before were there. Despite the heat, I saw Gora was still wearing

my sweater, and I swear I saw him smile at me just once."

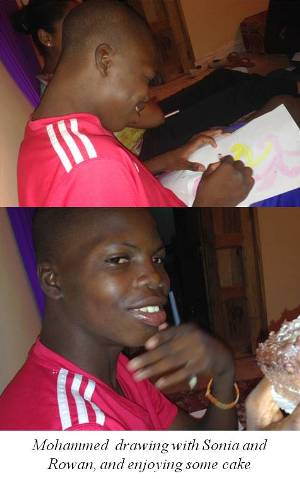

During our most recent trip, Maison de la Gare was caring for four other

runaway talibés in Issa's small apartment. Rowan and I brought a take-out

meal and colouring supplies and settled in for the evening while Issa had to

be out of the house for a meeting. Each child has his own story. But what

they have in common is that they are all children denied their basic human

rights. And they are denied what all children need, attention and affection.

Mohammed is a fifteen year old boy. He is from Dakar, and he came to

Saint Louis to work. He seems even younger than his age, and was soon being

exploited. He loves to draw. Mohammed drew pictures of a marabout whipping

a crying child, and of crying children holding insufficient coins for their

quotas in their hands.

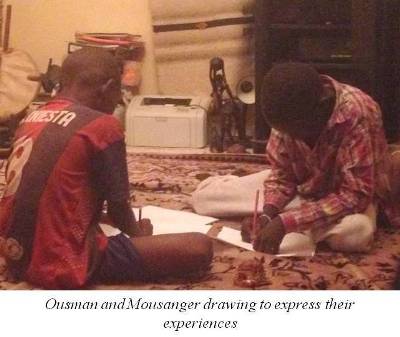

Ousman, about age 8, and Mousanger, age 12, were picked up by the local

police for stealing. Talibé children who are desperate to meet their quotas

may resort to stealing to avoid feared consequences. The police had entrusted

the children to Issa. Both boys thoroughly enjoyed their meals and the company.

They both drew picture after picture of the food we ate that night, offering

some of the drawings to us as gifts.

The most heartbreaking case was Pape, a child of only five years. He had

severe injuries on his ankles where his marabout had kept him chained for days.

His situation is considered severe and the police have called his marabout to

present himself for questioning. The marabout, however, has made himself

scarce. Perhaps the marabout will reappear once the wounds have had a chance

to heal and he considers the evidence erased. Issa's photo record will be

waiting. Pape was shy and quiet. He drew many pictures of his village and

clearly indicated

The most heartbreaking case was Pape, a child of only five years. He had

severe injuries on his ankles where his marabout had kept him chained for days.

His situation is considered severe and the police have called his marabout to

present himself for questioning. The marabout, however, has made himself

scarce. Perhaps the marabout will reappear once the wounds have had a chance

to heal and he considers the evidence erased. Issa's photo record will be

waiting. Pape was shy and quiet. He drew many pictures of his village and

clearly indicated  his desire to go home. He climbed quietly into my arms and

settled in for a snuggle too long denied him. He stayed with me, leaning

close for hours, and was disappointed to be gently laid on his mat when it

was time for Rowan and I to leave.

his desire to go home. He climbed quietly into my arms and

settled in for a snuggle too long denied him. He stayed with me, leaning

close for hours, and was disappointed to be gently laid on his mat when it

was time for Rowan and I to leave.

Rowan gave friendship bracelets to each of the boys to remember us by. They

wore them proudly. We will think of them as they navigate their challenging

lives in the days and years to come. At least we are comforted by the

knowledge that Maison de la Gare, at least, watches out for children such

as these, and will do all they can to guide them on their way.