News from Maison de la Gare

Miracle in the Desert

Tweeter

... seeing these children ready for exams feels like witnessing a miracle

(as told by Sonia LeRoy, Canadian partner of Maison de la Gare)

As we left the hotel behind us it was still dark. The crow of a rooster announced the new day

about to break. The car was waiting. Our guide, Cheikh Diallo, was just arriving from morning

prayers at the mosque. We stopped to pick up Issa and Boubacar on

the other side of the Saint

Louis’s landmark Pont Faidherbe, and we were on our way.

the other side of the Saint

Louis’s landmark Pont Faidherbe, and we were on our way.

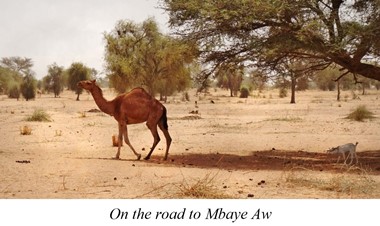

At Louga we left the highway and turned inland, toward Dahra Djolof. The sun had risen. The

sandy breeze flowed through the open windows of the van, and most of the heat of the day

was still in reserve.

After about three hours we stopped in Dahra Djolof to pick up our bush guide, Omar. He would

ensure we not lose our way in the desert bush. The first hour of the road was so potholed we

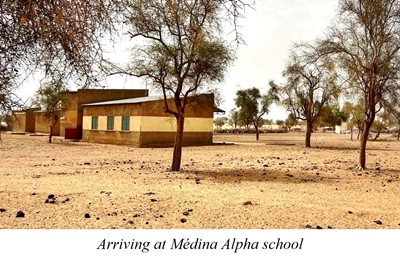

mostly drove on the sand. Then we turned off even that road. We eventually arrived at the

region of Mbaye Aw. Our first stop was the Médina Alpha school. This was the first of the schools

that Cheikh has organized in the region, with Maison de la Gare’s support. The only

one so far to be built of cement.

As we left the vehicle, villagers began to make their way curiously toward us from distant huts.

Parents, some past students, and some current students were in the group. Class was not in

session, as the teachers and many of the students are currently in Dahra Djolof writing government

exams. We asked if the past and present students would allow us to photograph them in front of

the school. A parent phoned the village elder who came to observe the situation. After a

discussion with Cheikh, he granted his permission.

After the pictures were taken, more villagers who had initially been reluctant to be photographed

insisted we re-take the photo, as all who were present now wanted to be included.

Fifty-seven students attend this school, boys and girls. The students who had advanced as far as

they could (about five or six years of education, before travelling far

afield would be required

to continue) spoke good French.

afield would be required

to continue) spoke good French.

Four of the other five schools are built of straw and are reinforced or rebuilt by the villagers

after each rainy season. One is not yet built; the teacher and students gather under a tree to

teach and learn. Interestingly, after a few years of classes at the cement school in Médina

Alpha, the government accredited the schools and sent a government teacher. Proving that there

is no need to wait and hope that authorities will build schools where schools have never been

and are not likely to be … if we build it, they will come!

After a wonderful meal, tea, and a peaceful visit in Cheikh’s idyllic, traditional village, we

got back in the car for the several hours drive, directed by Omar, through the desert to Dahra

Djolof to meet the sixty-five students, their guardians and teachers.

A large house had been rented for the purpose of housing these students. A teacher, several

parents, a supervisor, and a few cooks from the villages all stayed together to watch over and

tend the children as they prepared for and wrote their exams over several weeks.

When we arrived, we were invited to enjoy our second meal that day. This time, thieboudienne,

the Senegalese national dish. Then we were introduced to the children who were divided into

three groups to meet us, the boys, the young girls and the older girls. Several people made

speeches about the importance of education, the success of this school program in remote villages,

and hope for the future.

I was introduced as a partner who helped make this possible. I was invited to speak, and I seized

the opportunity to deflect praise toward the truly deserving recipients: the Senegalese who

conceived of and founded Maison de la Gare (Issa Kouyaté), the Senegalese founder of the Mbaye Aw

schools project (Cheikh Diallo), and all the staff and leaders of Maison de la Gare who never

cease their efforts on behalf of the begging talibé children of Senegal.

Then we got to meet the kids and take pictures with them. It is incredible to realize that these

bright, articulate, eager students had never had the opportunity to attend school until the five

schools were built. Twelve of the boys writing exams are returned talibés who used to be forced

daily to beg on the streets for quotas of money. But, several years ago, these boys had returned

because now there was a school to attend. Few families now send their sons from these villages

to becomes talibés. A marabout has even returned to teach the Quran traditionally, village-based,

while the children live at home, cared-for by their families.

Meeting the girls was just as inspiring. They work the hardest and are the most dedicated to

their studies. Never having had the opportunity for an education of any kind, they seem thirsty

for more. They recognize the opportunity education offers. Before the schools, their expected

path was a child marriage; we invite you to

read our earlier report, “A Travesty against Humanity,” to get a sense of

what a miracle it is that these girls are now in Dahra Djolof writing exams. The words and fears

and hopes that these girls shared will always remain with me.

The Mbaye Aw school project is a success. Accessible, village-based schools are so clearly a tool

for not only education, but also for ending the modern slavery of the forced-begging talibé boys

and of the forced early polygamous marriage of young girls.

________

Afterword – Cheikh has just reported that 31 of the 34 boys taking government exams were

successful, including 11 of the 12 returned talibés. 30 of the 31 girls were successful.