News from Maison de la Gare

A Family Affair

Tweeter

Sonia LeRoy shares the story of her family’s journey with Maison de la Gare

As soon as I arrived at the narrow,

unmarked alley in the Sor district of Saint Louis, leading to Maison de la Gare’s

welcome centre, I heard my name being called and spotted six familiar faces. Small,

barefoot, filthy,  delightful, smiling street boys. The clamor and dusty chaos of the

busy street receded as each child rushed forward for a proper hand clasp greeting.

Several repeated my name, wanting to ensure I knew that they know me. Their welcoming

smiles grew bigger when I began to pass out candy and the group of six instantly,

miraculously, became a demanding horde of twenty. When will I learn? Some of the

original six shook their heads at me knowingly. They accompanied me down the alley,

leading me by the hand, touching my arm, sneaking more shy smiles, and repeating

their own names, anxious to confirm that I also knew them.

delightful, smiling street boys. The clamor and dusty chaos of the

busy street receded as each child rushed forward for a proper hand clasp greeting.

Several repeated my name, wanting to ensure I knew that they know me. Their welcoming

smiles grew bigger when I began to pass out candy and the group of six instantly,

miraculously, became a demanding horde of twenty. When will I learn? Some of the

original six shook their heads at me knowingly. They accompanied me down the alley,

leading me by the hand, touching my arm, sneaking more shy smiles, and repeating

their own names, anxious to confirm that I also knew them.

Upon entering the sanctuary of Maison de la Gare, all I saw were smiles and all we

felt was welcome. "Sonia!", "de retour!", "combien de temps cette fois?", "et la

famille?", "et Robbie cette fois?", "Rowan?" It takes hours to greet everyone

properly, re-confirm their understanding of their importance to me and mine to them.

To be updated on recent illnesses, abuses and triumphs.

their understanding of their importance to me and mine to them.

To be updated on recent illnesses, abuses and triumphs.

The progress at the centre is encouraging. The coconut trees have finally taken

hold, no longer in danger of succumbing to stray soccer balls or wrestling children.

The papayas have survived the season of wind and sandstorms to stand tall and bear

fruit. The nurse in the infirmary will help organize the medications we

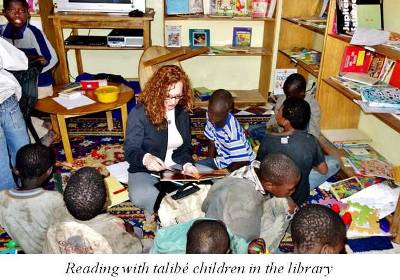

brought to stock the clinic. The children attend class, play games, tend the

garden, wash clothes, read in the library, follow their interests and friends on

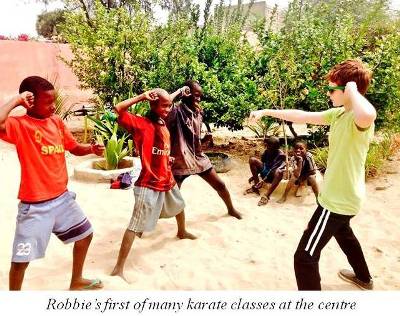

Facebook at the computer centre, and karate classes continue.

Souleymane, whom I love as family, proudly announces earning his orange karate

belt and his commencement of sparring competition. Arouna, another I love as my

own, updates me on the progress of his hard earned education. He is finally

attending high school but, although freed from forced begging, still has to deal

with the domination and interference of his marabout. Arouna dreams about

university, of teaching  and writing, anxious to himself become an agent of change.

I dream about finding him a scholarship to help make it happen.

and writing, anxious to himself become an agent of change.

I dream about finding him a scholarship to help make it happen.

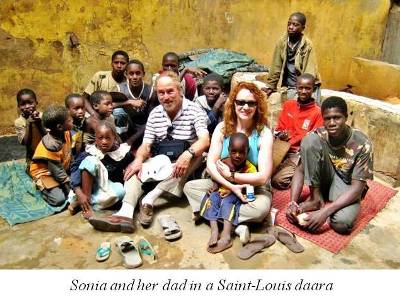

The very first time I made this journey with my father in 2010, I had no idea

what to expect. I had always longed to step outside my comfort zone to give back

to those without any resources to help themselves. Thanks to my father's

invitation to join him on his third trip to Senegal, I was getting the chance

to do just that. We were flying toward a level of poverty and human rights abuse

beyond my experience or comprehension. How could I, a person who leads people to

take control of their money in support of life objectives, have anything to offer

to those without a penny in the world or objectives other than survival?

I quickly fell in love with these children, their beauty, resilience and humour,

all in the face of unimaginably intolerable circumstances. They are known as

talibés. There are tens of thousands of them in Senegal, all boys. They are

supposed to be studying the Quran, but instead are forced to beg for quotas of

money for their marabouts. Often severely abused and neglected by distant

families, talibés beg for up to ten hours a day. Human Rights Watch and the

United Nations refer to the talibés as modern day slaves. The government and

society in general turn a blind eye. Someone else is always to blame: the

government, parents, the marabouts, police who fail to enforce the law. No one

but Maison de la Gare seems willing to take responsibility for these innocents.

a blind eye. Someone else is always to blame: the

government, parents, the marabouts, police who fail to enforce the law. No one

but Maison de la Gare seems willing to take responsibility for these innocents.

The first time I encountered a talibé child the age of my own son and nephews,

I had an overwhelming sense that, but for the grace of God or an accident of

birth, these could be my own children. And, if I could help them, I knew that

I must. What makes me, or any of us in the West, any more deserving of

prosperity, health, security, opportunity and hope than these children who have

perpetrated nothing to earn their circumstances but be born in this time and

place.

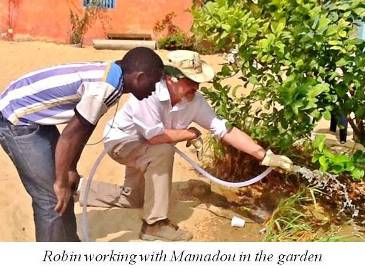

Since that first visit I have returned a dozen times to continue to work with

Maison de la Gare, often with my father, to help build the center according

to founder Issa Kouyate's vision and to do what I can to help the Senegalese

staff help the children to maintain hope and find a way to a better life.

Over the years at Maison de la Gare, I have taught the children English,

French and karate. I have been a project manager and a tour guide. I have

tended wounds and de-wormed kids in the daaras and in the health clinic. I

have been a gardener, a painter, a labourer, a mentor and a mother and a

friend. My family's charitable foundation and my Dad's grant writing

patience facilitates the funding of much of the progress here, funded with

the help of many  sympathetic contributors. All of the investment companies

I work with have contributed. My Dad manages the books and maintains the

website that helps fuel more donations and a thriving international volunteer

program. We both write regular articles to keep the donations flowing. And,

all the while, these children have truly become a second family to us.

sympathetic contributors. All of the investment companies

I work with have contributed. My Dad manages the books and maintains the

website that helps fuel more donations and a thriving international volunteer

program. We both write regular articles to keep the donations flowing. And,

all the while, these children have truly become a second family to us.

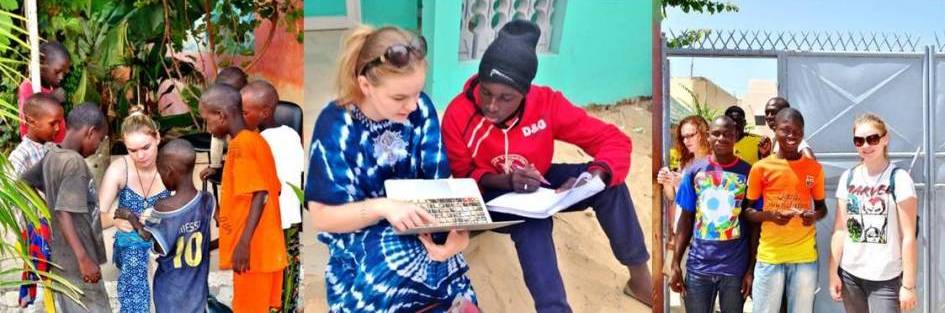

Four years ago my then 14 year old daughter, Rowan, accompanied me to Senegal

for the first of five times (so far). She connected with the talibés in a

manner that only a young person could do. Rowan saw the talibé children as

equals, with the same unlimited potential that she knows herself to have.

She saw them in a way they likely had never seen themselves, never

considering potential limitations of kids who could barely read or write or

had never seen a computer. Rowan helped establish email accounts for the

talibé children. She knew that a connection with the outside world and with

herself back in Canada, the possibility of maintaining long term links with

international volunteers, regular exposure to different world views, and the

acquisition of skills valued by modern society could benefit the talibés

immeasurably. These are surely now the most on-line-savvy begging street

kids in Africa!

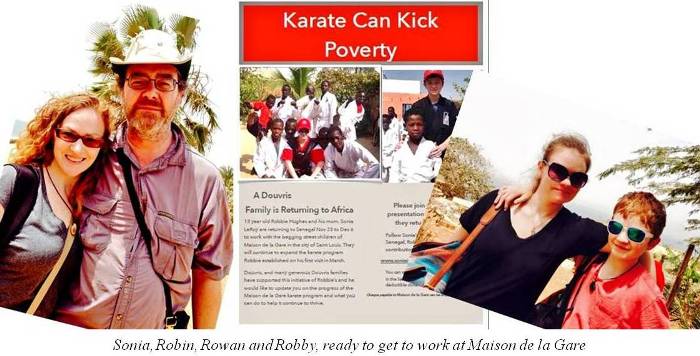

A year and a half ago, my husband Robin and my son Robbie joined Rowan and

I on their first visit to volunteer with Maison de la Gare. Then

13-year-old Robbie, like Rowan before him, envisioned possibilities for the

talibés that most adults could not have conceived of. Appreciating the

advantages his sport of karate has to offer the talibés, discipline,

confidence, self-defence skills, and the sense of belonging to something

special, Robbie convinced us to facilitate a karate program for the talibés

of Maison de la Gare. Today, the pride the boys take in their white gi

(karate kimonos) and belts, donated from Canadian dojos, is evident.

During Robbie's second visit with me last December, we were invited to

watch some Maison de la Gare talibés earn higher belts. Their confidence

was palpable, and their pride in achievement was irrepressible. Robbie

with his black belt, who is of an age with many of them, is an example and

helps to spread the belief that anything is, indeed, possible.

Even for talibés.

Perhaps the most impact we have on the children of Maison de la Gare lies

simply in our example,  and our interest. Maison de la Gare tries to teach

them they are worthy of so much more. The simple presence of

international volunteers underscores this truth. And, the presence of

children competently volunteering demonstrates to the talibés how

powerful kids can be.

and our interest. Maison de la Gare tries to teach

them they are worthy of so much more. The simple presence of

international volunteers underscores this truth. And, the presence of

children competently volunteering demonstrates to the talibés how

powerful kids can be.

My family and I ventured to Africa in search of giving. And, I know we

did. I know it for the progress I see: the smiles on the faces, the

amputations averted thanks to antibiotics, the enrolments in school, the

philosophical conversations started about society's role in forced

begging, the pride in achievement, the white karate belts transforming

to coloured belts, the late night emails received and Facebook chats I

am invited to every time I am on-line. But what we receive is far

greater. Interacting with these kids not only inspires me that absolutely

anything is possible, it gives me a sense of being completely present

and alive. It has transformed my and my children's paradigms. No one

does this work in order to receive. But, it is inevitable, as anyone

who gives knows.

Volunteering with Maison de la Gare as a family has brought unimaginable

gifts to us. Doing this work together as a family has brought us closer

together and has helped us better appreciate our own advantages and

opportunities while expanding our perspectives on just about everything.

International volunteering can be successful and rewarding for anyone.

Students, retirees, couples, youth groups, individuals and now families

have left their mark on Maison de la Gare. And Maison de la Gare, its

dedicated staff and founder Issa and the talibés of Saint Louis have,

in turn, left their mark on every volunteer who has stepped through

their doors.