News from Maison de la Gare

Talibé Children Discover Their History

Tweeter

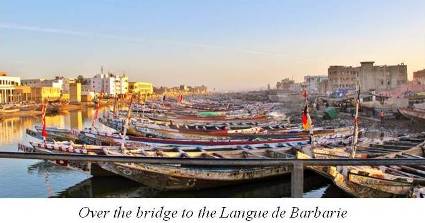

Sonia LeRoy reports on a horse-drawn carriage ride around Saint Louis that became a window on the past

Maison de la Gare is a place where

talibé children have the opportunity to learn, as well as to

just enjoy being children

while being appreciated as the unique individuals they are. This recently manifested

itself in a unique way for the begging street children of Saint Louis.

just enjoy being children

while being appreciated as the unique individuals they are. This recently manifested

itself in a unique way for the begging street children of Saint Louis.

A group of Canadian high school students, each with a parent (myself one of them)

organized a unique excursion for the talibés of Maison de la Gare. The excursion was

at once an outing to relax far from their daily trials of forced begging, while at the

same time being an opportunity to bond with the volunteers and to spend time

experiencing a tour and seeing local historical sights. And, these talibés learned

about the history and heritage of the city in which they live, in many cases for the

first time.

opportunity to bond with the volunteers and to spend time

experiencing a tour and seeing local historical sights. And, these talibés learned

about the history and heritage of the city in which they live, in many cases for the

first time.

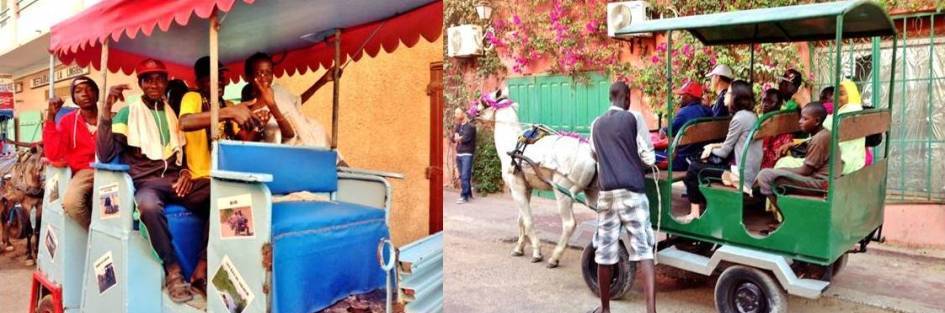

Initially it was planned that sixteen talibé children, their Maison de la Gare teacher

Bouri Mbodj and the volunteers would participate. When our group met at Maison de la

Gare's center to gather for the walk to the tour departure point on the island of Saint

Louis, the group of interested talibés had become 26. A few more Maison de la Gare

talibés joined the group as we walked and, by the time we prepared to board the horse

drawn carriages to begin the tour, our group had swelled to 35.

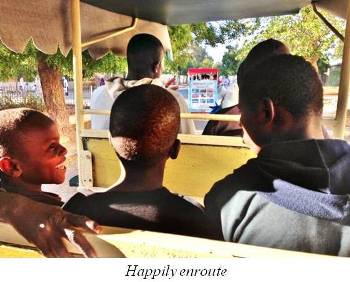

As the tour progressed,

two more stragglers hopped on. Only four carriages had been ordered for 23 people.

However, all 35 squeezed happily into the carts, with the little ones balancing on the

laps of adults and teenagers. Only the hard working horses were unhappy with the situation.

As the tour progressed,

two more stragglers hopped on. Only four carriages had been ordered for 23 people.

However, all 35 squeezed happily into the carts, with the little ones balancing on the

laps of adults and teenagers. Only the hard working horses were unhappy with the situation.

As we set out on our journey, behaving like tourists, bystanders gaped in astonishment

as they realized it was mainly talibés on board, some barefoot

and filthy, but with

beaming smiles emanating pride and happiness. Many held our hands, enjoying moments

of affection as might a parent and child on a family outing.

and filthy, but with

beaming smiles emanating pride and happiness. Many held our hands, enjoying moments

of affection as might a parent and child on a family outing.

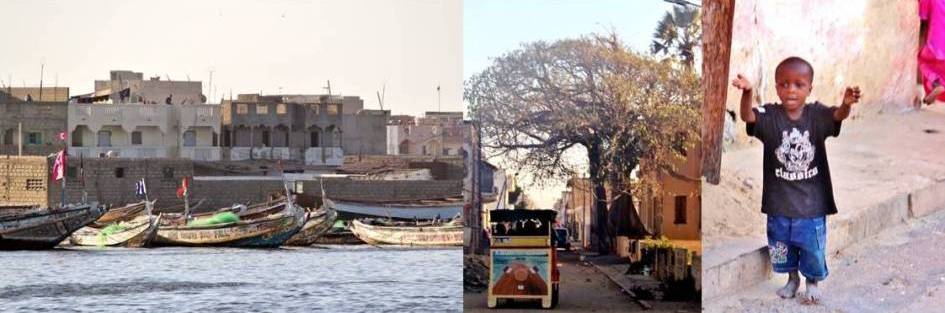

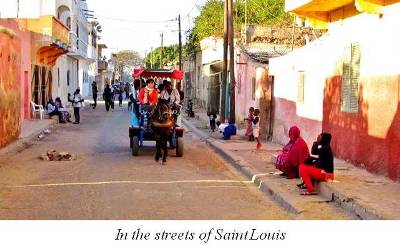

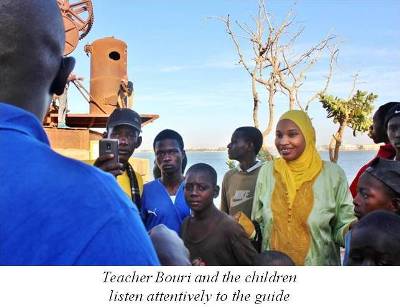

At each point of interest, the group disembarked for a history lesson. The information

was repeated in French as well as Wolof by our thoughtful guide, to ensure that the

talibés understood. Most of the talibé children had never crossed the bridge to the ocean-side

Langue de Barbarie;  a few had never before ventured even onto the island of Saint Louis,

remaining forever in their familiar begging grounds of Sor on the mainland, a 500 meter

footbridge away.

a few had never before ventured even onto the island of Saint Louis,

remaining forever in their familiar begging grounds of Sor on the mainland, a 500 meter

footbridge away.

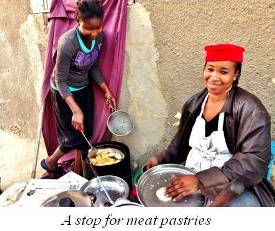

At one historical stop, meat pastries were being fried and offered for sale at a

roadside stand. The children were delighted to be treated to a pastry each for dinner.

As a description was offered of the riverside colonial warehouse that in past centuries

housed the trade goods of ivory, rubber, gold and slaves, one child asked: "What is

a slave?" Sober and astonished silence descended as the guide explained, as gently

as possible, the history of the transatlantic slave trade in Senegal.

Most of these

kids had never heard of slavery, and could not absorb even the concept of the barbarism

that dominated four centuries of their own history. Watching these children whom the

United Nations defines as modern day slaves trying to accept such historical horrors,

I was struck by how little had, in fact, changed from those difficult times for these

beautiful talibé boys.

Most of these

kids had never heard of slavery, and could not absorb even the concept of the barbarism

that dominated four centuries of their own history. Watching these children whom the

United Nations defines as modern day slaves trying to accept such historical horrors,

I was struck by how little had, in fact, changed from those difficult times for these

beautiful talibé boys.