News from Maison de la Gare

A Prison for Children

Tweeter

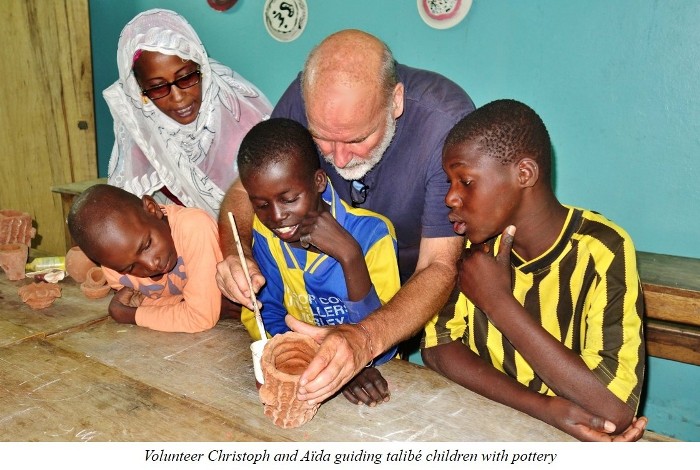

Volunteer Christoph Pauly discovers the sad reality in a daara

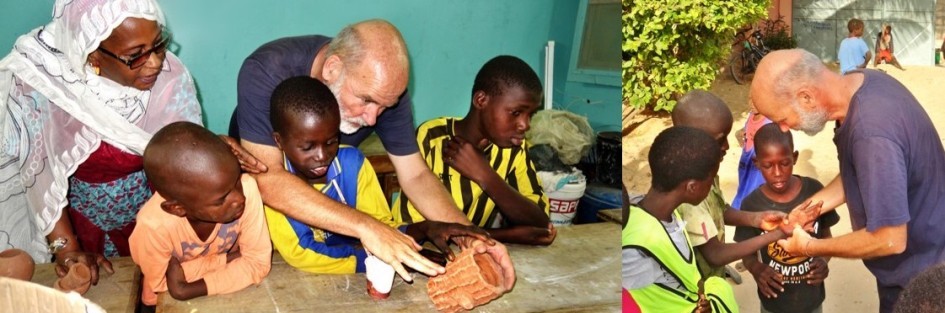

"I had worked as a

volunteer with Maison de la Gare and talibé children for weeks. I was touched by the boys’

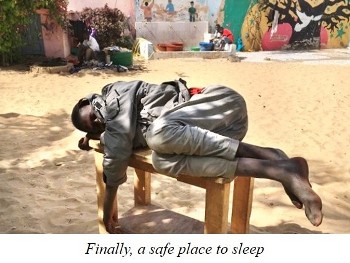

joy in the small things that Maison de la Gare’s peaceful center offers. A bench to rest

on, running water to wash and a book to get lost in the realm of

fantasy, even if you can’t

read. Their absolute will to take on what life throws at them. This existential hunger for

a smile, for a soccer ball, for a piece of bread filled with sauce before leaving for the

night on the street, before entering their marabout’s daara.

fantasy, even if you can’t

read. Their absolute will to take on what life throws at them. This existential hunger for

a smile, for a soccer ball, for a piece of bread filled with sauce before leaving for the

night on the street, before entering their marabout’s daara.

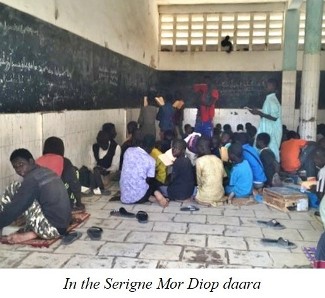

But it is in a daara that I really started to understand. Daaras are houses run by an

Islamic teacher, a marabout, where children are supposed to get an Islamic education.

These places, which often operate like businesses, force children to beg on the streets to

earn a living, but also to support their marabouts.

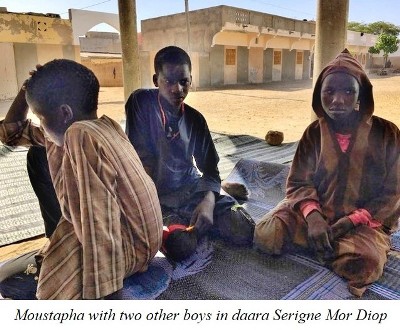

Moustapha, about 10 years old with clean clothes, a closed face and sad eyes, is sitting

with two other children in front of us. ‘Yes, everything is fine,’ he says to us in a

weak, almost inaudible voice, when Aby asks him how he is doing. He looks at his marabout

with fear; he seems anxious not to make a mistake, not to tell the truth. The young

marabouts are also present with their little whips.

They supervise the daily work of

talibés and enforce discipline. I had never seen Moustapha at Maison de la Gare.

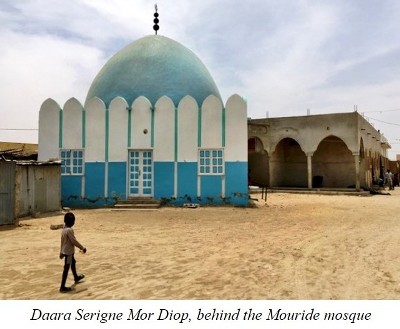

However, this is not surprising. Indeed, according to what the marabout tells us, the

boy has not been allowed to go out since his escape from the daara - Serigne Mor Diop in

Pikine near the Saint Louis bus station.

They supervise the daily work of

talibés and enforce discipline. I had never seen Moustapha at Maison de la Gare.

However, this is not surprising. Indeed, according to what the marabout tells us, the

boy has not been allowed to go out since his escape from the daara - Serigne Mor Diop in

Pikine near the Saint Louis bus station.

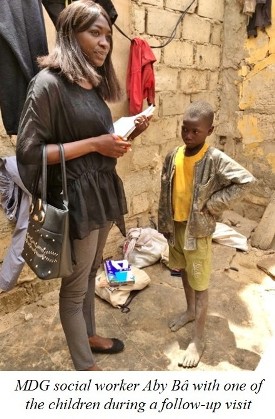

Aby, a social worker at Maison de la Gare, once again kindly asks Moustapha if he plays

in his daara. He doesn’t answer anymore. A tear falls from his eye. His face remains

closed, hard, prematurely adult; this time the stress is too great. I watch the tear

slowly descend to his chin, in absolute silence. I feel uneasy in the face of this

suffering. ‘When did you last see your parents, Tapha?’ It is not him but his marabout

who answers us, triumphant: ‘Three weeks ago all the parents came to the daara and they

were very happy.’

Élodie, a young Belgian psychologist, is also touched by this drama unfolding before our

eyes. ‘Can we talk to him alone? Maybe only one afternoon at Maison de la Gare?’ The

marabout doesn’t answer. According to him, he is the only one who can take care of the

child and teach him the Koran.

Aby invited us to join her for this follow-up visit to the daara. Maison de la Gare

regularly visits children like Moustapha who have run away or have been found abandoned

in the streets during the night. ‘Often children choose to go back to their daara

because parents do not want them anymore or because they do not have families to go

back to,’ says Aby.

Maison de la Gare tries to cooperate with the marabouts, to change their attitudes.

A delicate mission! During this visit, it becomes clear that Souleymane is in an

internal prison with many other children. The marabout prefers to speak of a boarding

school: ‘The children have the right to go out once a week with their guardian.’ I

answer him: ‘At home, even prisoners who have committed capital crimes can go out at

least once a day in the prison yard.’ What is the crime committed by these children?

Where are their basic rights? We want to see inside this internal prison. However,

the marabout does not let us enter his daara of 500 children, one of the biggest in

Saint Louis.

not let us enter his daara of 500 children, one of the biggest in

Saint Louis.

When we return we talk to Issa, Maison de la Gare’s president. He is alarmed, just as

we are. Of course, it is against Senegalese and international laws to lock up children

in a prison. This would not be the first time Maison de la Gare has sued marabouts in

court; some have even chained children in their daaras. Issa speaks with court

officials about our case. Finally, it is the sub-prefect of the Saint Louis region

who shows interest. Daara Serigne Mor Diop has links with the Mourides, a very

powerful brotherhood in Senegal.

But Moustapha and the other children I met in this daara do not leave me in peace. On

my last day in Saint Louis, I again accompanied Aby to visit this immense daara in the

religious district of Pikine. A place enclosed with a wall with an imposing mosque,

almost like one of those so powerful cloisters of the Middle Ages

at home in Europe.

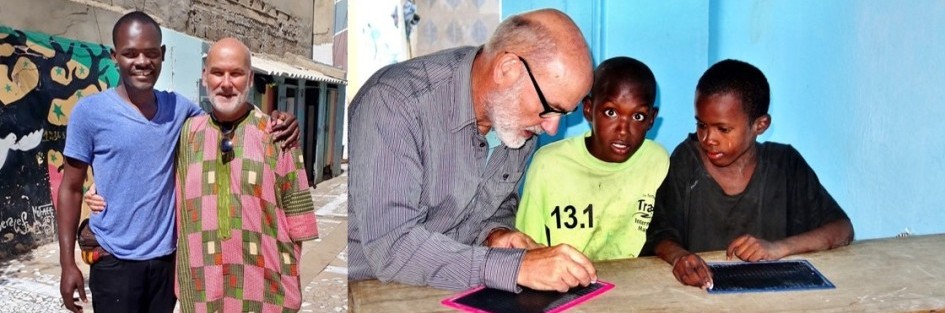

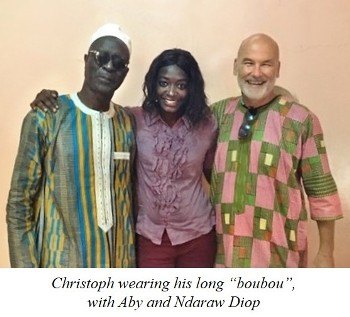

This time, I wear a long boubou that shines with the colors of Africa. One of those

traditional capes that marabouts also wear, although with darker colors.

at home in Europe.

This time, I wear a long boubou that shines with the colors of Africa. One of those

traditional capes that marabouts also wear, although with darker colors.

Moustapha and the two other boys we visited last time are allowed to meet us. The same

stoic faces, closed, but this time no tears. The marabout and the boys say that they

were able to leave the prison. Apparently, our interest in their fate has helped them

a lot. The marabouts understood that we wanted to know, that Maison de la Gare knows

about these children, that we will not close our eyes, that we would confront them with

their responsibilities.

Then, I wanted to see the prison. This time the marabout changes his mind. Was it my

boubou that changed the game? The sub-prefect? My insistence? He lets me enter the

daara. Unfortunately, Aby is not allowed in because she is a woman.

Behind the door, a vast courtyard with several rooms where there are a hundred children

who move to the rhythm of the psalms of the Koran, the books in Arabic in front of them.

And there is a black door with a small window. ‘Behind this door is the prison,’ a

young marabout tells me.

rhythm of the psalms of the Koran, the books in Arabic in front of them.

And there is a black door with a small window. ‘Behind this door is the prison,’ a

young marabout tells me.

After a five-minute wait, the steel door opens from the inside. The guard turns the

key; they do not do this very often for visitors. A little sun provides light in the

courtyard. The door closes behind me. I see a large room with about fifty children

sitting on the carpet where they learn, play and sleep. Many young children five, six

or seven years old. Some older. Many watchful eyes on me, calm, not daring to even

hope. In the middle of the room, I see plastic bowls filled with food which the other

talibés have collected in the streets.

At first, I am relieved. No chains. No blood. Not in the dark. But, these children

can’t go out; they are deprived of their liberty, sometimes for months.

Because they

are too young, because they fled their daara, because they were not disciplined enough.

I let them show me the "showers", a tiled basin without running water. And four

toilets, holes with a nauseating odor.

Because they

are too young, because they fled their daara, because they were not disciplined enough.

I let them show me the "showers", a tiled basin without running water. And four

toilets, holes with a nauseating odor.

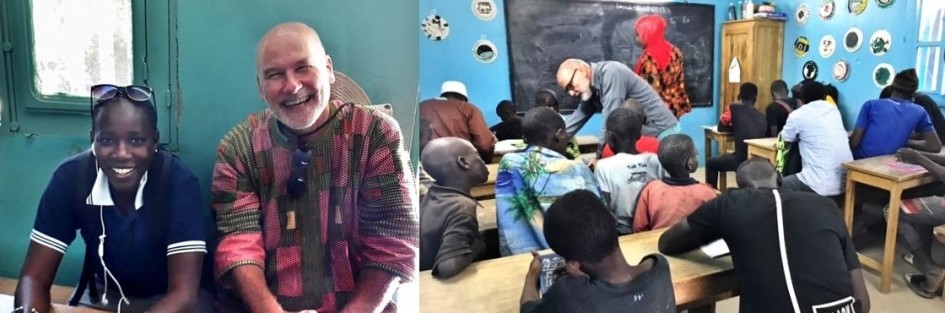

Finally, I understood many things. If these young boys some day are given the right

to go out on the streets, they will be happy to beg or to work hard for their marabout.

To feel the freedom of the street, even for a few hours of the day, is still better

than a prison. If by chance these traumatized boys find Maison de la Gare’s little

courtyard, they will feel like they are in paradise.

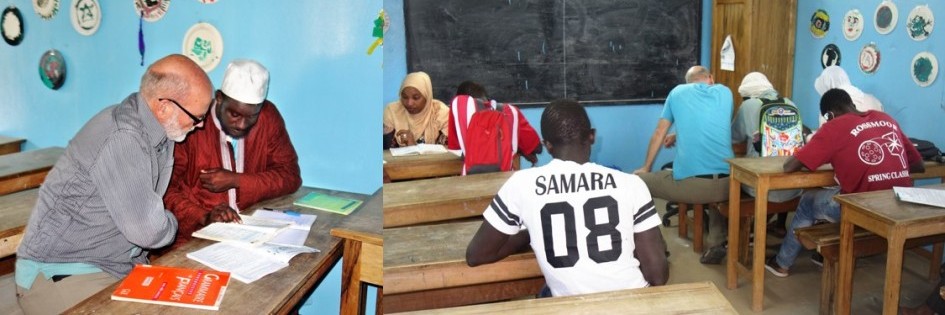

One of Maison de la Gare’s important obligations, for both leaders and volunteers, is

to continue to monitor children in the daaras, making sure they are well. It is also

important to confront Senegalese authorities with the truth. It is a fact that there

are prisons for children, and this medieval practice obviously goes against all national

and international laws."