News from Maison de la Gare

"Challenging and Difficult at Times, but Extremely Rewarding"

Tweeter

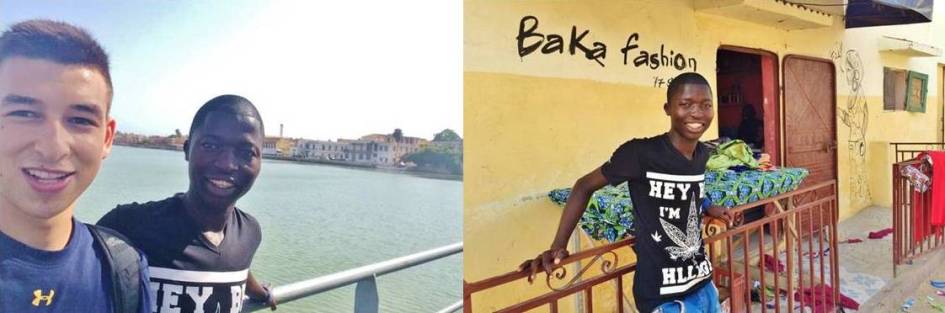

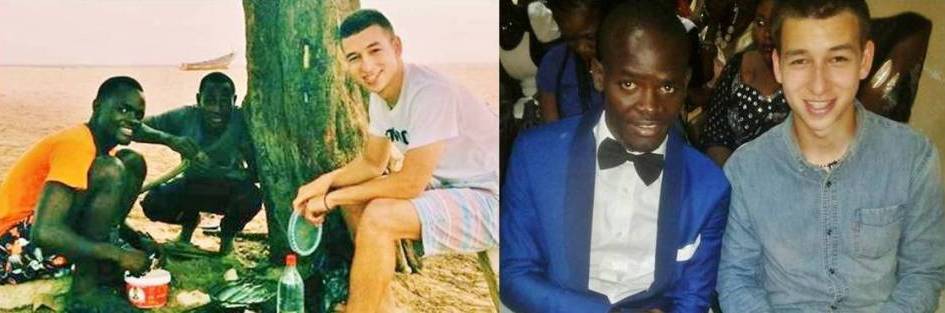

American Volunteer Liem Tu reflects on his two months with Maison de la Gare

Senegal can be a bit of an

overwhelming place at times. My morning walk from my homestay to Maison de

la Gare’s center was an experience in itself. The cacophony of sounds that

fills the air is unlike any place I’ve ever been: the high-pitched honks of

taxis trying to attract customers, the loud voices of chatting Senegalese

women as they tend  to their mango stands next to the road, enthusiastic

vendors holding out souvenirs for sale and greeting you with an over-the-top,

“Hello, my friend!!”, and little children yelling, “Bonjour, Toubab!” as they

pass you on the sidewalk, pointing and giggling at your sun-burnt,

sweat-covered skin. "Car rapides" whiz by, so filled with passengers that

young men hang off of the back, holding on for dear life. It’s always a

trip riding them - the buses have been aptly nicknamed “s’en fout la mort”

– French for “don’t care about death”.

to their mango stands next to the road, enthusiastic

vendors holding out souvenirs for sale and greeting you with an over-the-top,

“Hello, my friend!!”, and little children yelling, “Bonjour, Toubab!” as they

pass you on the sidewalk, pointing and giggling at your sun-burnt,

sweat-covered skin. "Car rapides" whiz by, so filled with passengers that

young men hang off of the back, holding on for dear life. It’s always a

trip riding them - the buses have been aptly nicknamed “s’en fout la mort”

– French for “don’t care about death”.

And, of course, wherever you are in the city of Saint Louis you will hear

the call to prayers  and sermons broadcasted in Arabic from the loudspeaker

of the nearest mosque. At this point, we’ve already heard four different

languages on our walk – Wolof, French, Arabic, and English. This is what

makes Senegal so unique; the influences of French colonization, strong

Islamic traditions and a tribal history have combined to create a complex

and rich culture unlike any other. For me, throwing myself into this

completely new and complicated environment was extremely fascinating but

also difficult at first. Difficult because I really did not understand

the culture when I arrived, and this meant I committed a lot of embarrassing

and awkward faux pas, leaving me feeling a little bit out of place.

and sermons broadcasted in Arabic from the loudspeaker

of the nearest mosque. At this point, we’ve already heard four different

languages on our walk – Wolof, French, Arabic, and English. This is what

makes Senegal so unique; the influences of French colonization, strong

Islamic traditions and a tribal history have combined to create a complex

and rich culture unlike any other. For me, throwing myself into this

completely new and complicated environment was extremely fascinating but

also difficult at first. Difficult because I really did not understand

the culture when I arrived, and this meant I committed a lot of embarrassing

and awkward faux pas, leaving me feeling a little bit out of place.

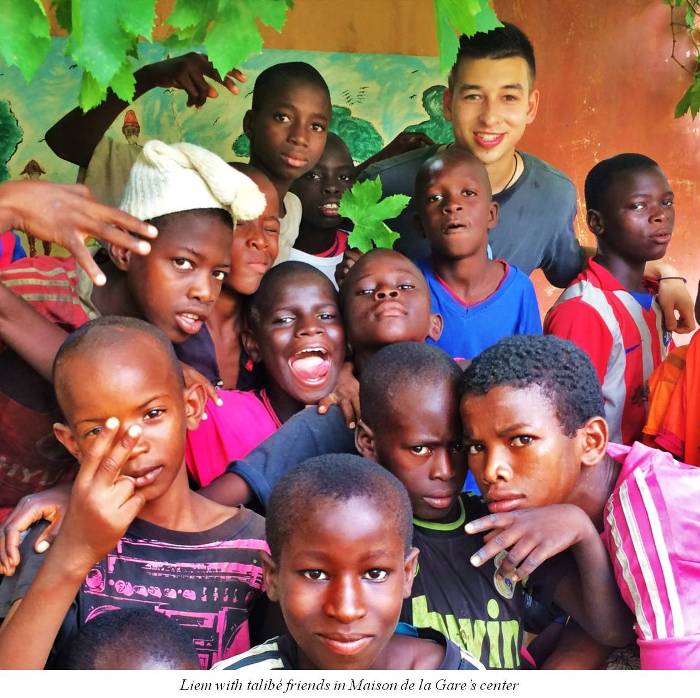

Maison de la Gare, however, was a place that I always felt at home – as

it is for many talibés as well. Part of it was the appearance of the

center. One can’t help but feel calm and relaxed sitting in the center’s

quiet garden with its banana trees and grape vines, looking out at the

colorful murals that cover the surrounding walls. But, in addition to

the garden, it was the people of Maison de la Gare who made me feel welcome

and comfortable there from day one, regardless of the cultural mistakes I made.

that cover the surrounding walls. But, in addition to

the garden, it was the people of Maison de la Gare who made me feel welcome

and comfortable there from day one, regardless of the cultural mistakes I made.

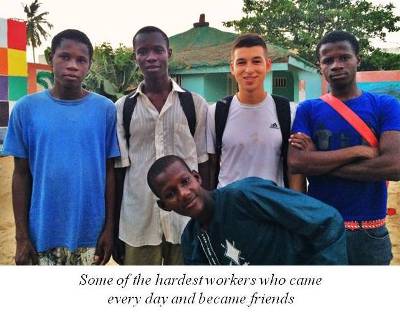

The first morning, and every morning after, I was greeted by smiles and

handshakes from everyone at the center. I was accepted. Then, it was the

work I did that began to give me confidence and a real sense of purpose.

One of Maison de la Gare’s staff members, Noël Coly, immediately showed me

how to take attendance electronically as the talibé children arrived at the

center each morning. With over 100 boys showing up daily, this was a great

way to meet them and learn their names.

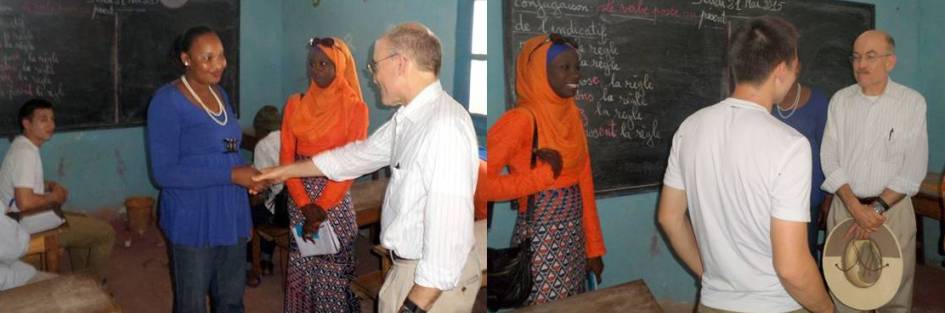

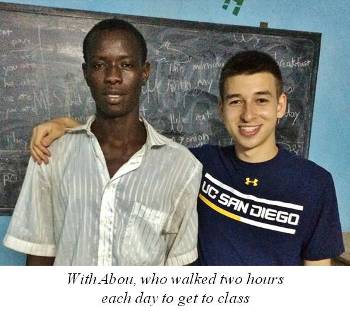

Other days I spent my mornings working individually with older talibé

children who wanted to improve their English, French, or math skills.

These sessions were really helpful because, for every word I taught in

English or French, the boys would teach me the word in Wolof. Besides

being helpful for my Wolof ability though, working with the boys was a

very inspiring experience. As I learned more about their stories, I was

continually blown away by the motivation and character they possess despite

their harsh circumstances. One student named Abou would walk for two hours

to get to the center every day, waking up at 4:00 am to fulfill his

responsibilities at his daara before leaving. There were many other

stories like this one. They humbled me and motivated me to work even

harder, while reminding me why I had come there.

In the evenings I would return to the center for the nightly language

classes. I began working with Omar, a Peace Corps volunteer who led

English classes for the older talibés (15 to 20 years old). Our classes

began at 6:30 p.m. and, because it was Ramadan, went until Ndogou at

7:30 p.m. – the time to break the fast. The boys, despite not eating

or drinking anything for 13 hours, were always positive, driven and

focused during class, always wanting to learn more and asking questions.

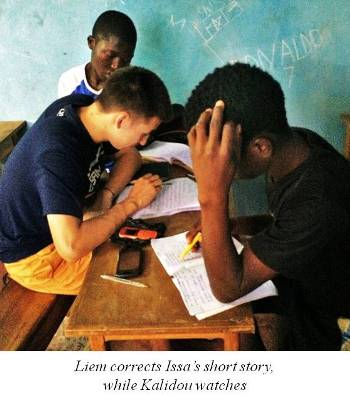

When I arrived, I was nervous about teaching. I had never taught a

language before, and I had no credentials or certification. When I

started, my limited Wolof speaking ability made it sometimes hard to

explain words or phrases. But I was lucky to have Kalidou in my class,

a talibé who spoke some English. Kalidou was a translator, a teacher

and a student, all at the same time – acting as a middleman between

the boys and me whenever we had trouble understanding each other.

Over time, I learned some Wolof too. The boys found it very amusing

and entertaining when I would attempt to explain things using the Wolof

words I knew. Although embarrassing, using my Wolof brought me closer

to the boys and erased a wall that could have developed between us.

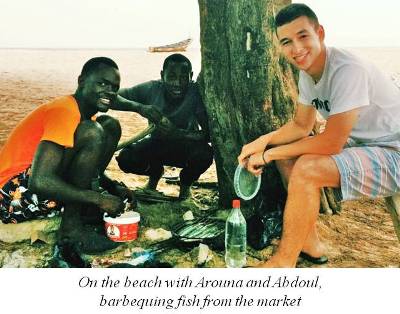

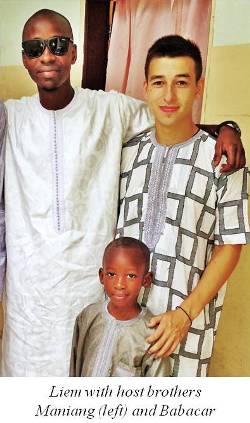

Outside of the classes and work, I spent a lot of time at the center

just having fun and talking to people. Playing ping pong with Bathe

and Abdou. Finding a pizza place with Diodio and Issa. Talking about

school with Arouna. Playing soccer video games at the local arcade

with Kalidou and Samba. Having these strong friendships gave me people

to share my experiences with, making it slightly more bearable to deal

with some of the sad and challenging aspects of working with the talibés.

I came to Senegal expecting to discover a new culture, gain experience

teaching, improve my French and support a cause that was bigger than me.

Looking back on it, I gained so much more. It sounds cliché, but being

in Senegal changed me in a way. Before coming to West Africa I, like

many Americans, had little understanding of how the non-Western world

works and struggles.  Being exposed to a different way of life and the

realities of living in a developing country made me reflect and

reconsider many aspects of my life at home.

Being exposed to a different way of life and the

realities of living in a developing country made me reflect and

reconsider many aspects of my life at home.

There were cultural differences that I just couldn’t figure out when

I first arrived, but over time they really became endearing. Now that

I’m back in the US, I kind of miss being able to eat rice with my hands

and greeting people Senegalese-style every morning.

But more than anything, I miss people and relationships. With Facebook

I chat regularly with the boys and staff members to stay in touch, but

it does make me sad to think that I may never see some of them again.

When I came back to the US, people often asked me, “Was it a good

experience?”. It’s kind of a complicated question, and at first I

had trouble determining what “good” really meant to me. I’ve had

some time to reflect on everything though, to put into words how I

feel. Now, I always respond, “It was challenging and difficult at

times, but it was extremely rewarding”.