News from Maison de la Gare

The City of Begging Children

Tweeter

Omar's Story - Spanish journalist José Naranjo tells the story of a child found living in the street, and of Maison de la Gare's work to stop this horror

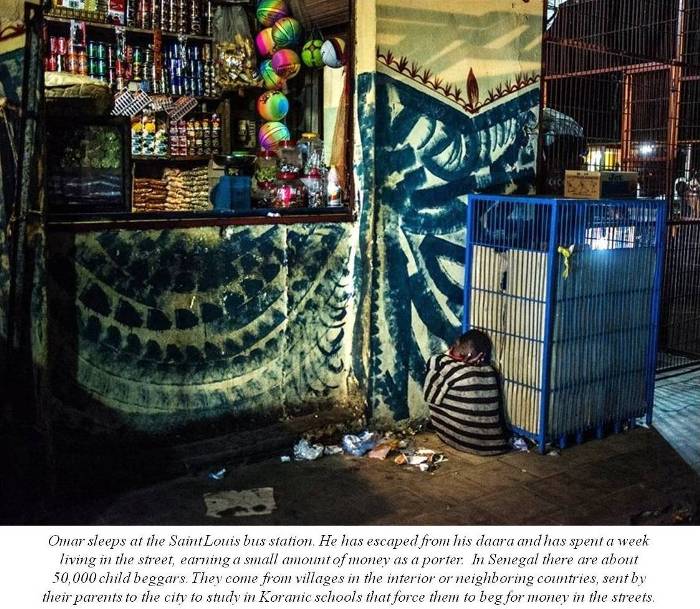

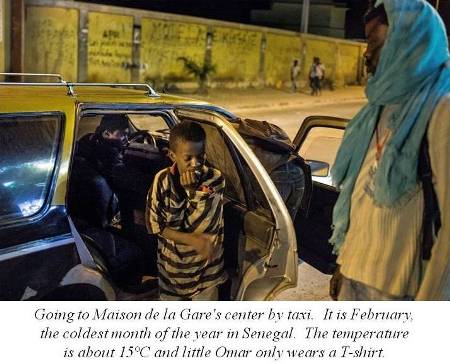

It is night. There is a black chill,

a chill that sneaks into the crevices of the soul. At the Saint Louis bus station, the

last travelers of the day wait for their buses while clinging to the minimal heat from

a cup of coffee. A small human bundle is visible beside the counter of a store selling

toys, soda and treats.  It is Omar, about ten years old, sleeping in his black striped

t-shirt, overcome by exhaustion. Everyone looks at him, nobody sees him. Like him,

about 15,000 children wander each day in search of alms in the streets of this city,

trapped in a spiral of tradition, poverty and the most crude child exploitation that

for Senegal, a tolerant, stable and growing country, represents both a shameful practice

and one of its greatest challenges.

It is Omar, about ten years old, sleeping in his black striped

t-shirt, overcome by exhaustion. Everyone looks at him, nobody sees him. Like him,

about 15,000 children wander each day in search of alms in the streets of this city,

trapped in a spiral of tradition, poverty and the most crude child exploitation that

for Senegal, a tolerant, stable and growing country, represents both a shameful practice

and one of its greatest challenges.

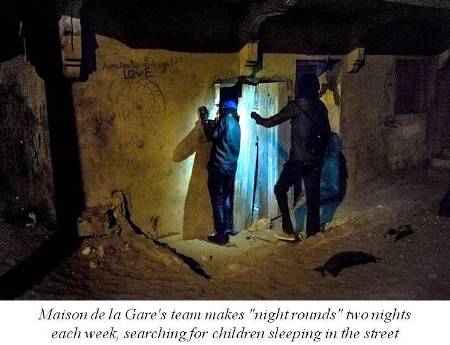

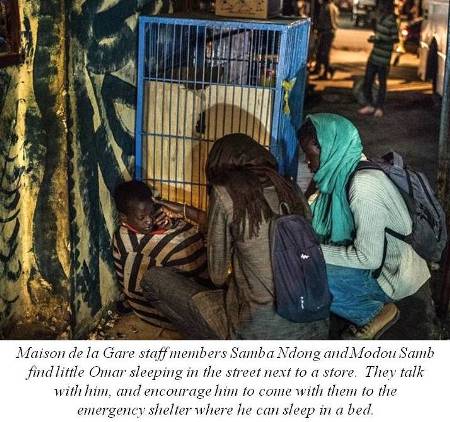

Modou Samb and Samba Ndong approach Omar, wake him gently, tell him that it is not safe

to be there, and encourage him to go with them. Omar looks up and watches them, sleepy

and surprised. His first reaction is to flee, scared, but he listens to what they say.

They talk about a bed, a shower, new clothes. Above all, a night of respite. How to

resist after a week of wandering aimlessly, taking refuge in any corner?

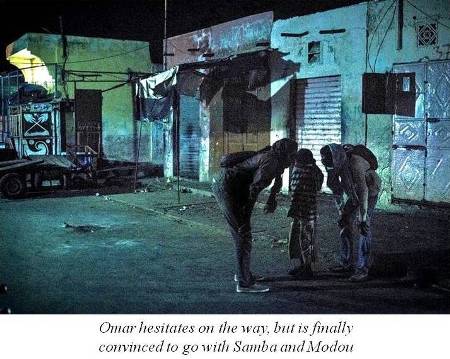

Downcast, terrified, confused, Omar walks along with his rescuers from Maison de la

Gare, three figures scarcely visible in the gloom of the night among the rickety

stalls. The child hardly speaks, only muttering some words in a low voice.

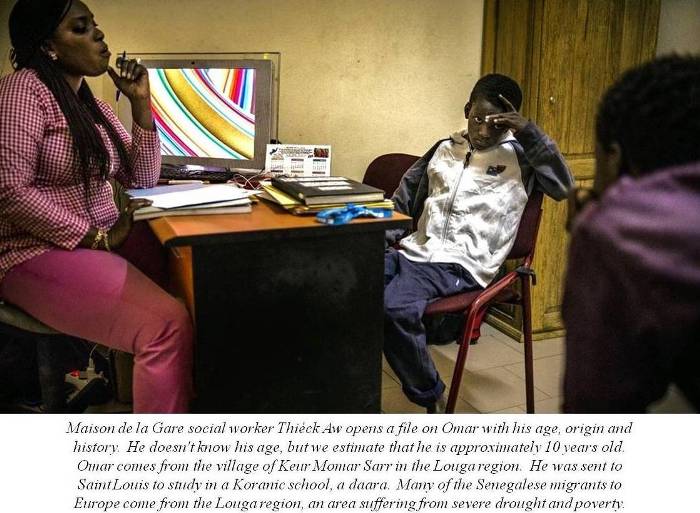

Coming from Keur Momar Sarr, a small village near Louga, Omar has been away from his

daara for a week. He had been there for five years, but fled when his marabout beat

him for being late one day. He has been earning a few miserable coins driving a cart

in the bus station. When they arrive at Maison de la Gare, Omar lies down on a bunk

bed and is covered with a blanket. A roof and a little affection, after all.

There are about 50,000 begging children in Senegal. They come from villages in the

interior or from neighboring countries like Gambia and Guinea Bissau,

sent by their

parents to the city to study in Koranic schools or daaras, where they are forced to

beg for money in the streets. What was once a system of learning of the Koran has

now become pure exploitation. Although not all Koranic schools make their children

beg, the reality is hard to hide: the talibés are the backbone of this army of small

beggars who fill Senegalese cities every day, and the money they collect sustains

their exploiters, marabouts without scruples who take advantage of the poverty and

illiteracy of rural families that entrust the children to them.

sent by their

parents to the city to study in Koranic schools or daaras, where they are forced to

beg for money in the streets. What was once a system of learning of the Koran has

now become pure exploitation. Although not all Koranic schools make their children

beg, the reality is hard to hide: the talibés are the backbone of this army of small

beggars who fill Senegalese cities every day, and the money they collect sustains

their exploiters, marabouts without scruples who take advantage of the poverty and

illiteracy of rural families that entrust the children to them.

What was once a system for learning the Koran has become pure and brutal

exploitation

As the new day dawns and Omar enjoys the warmth of his unexpected bed, thousands

of dirty children dressed in rags take to the streets with their begging bowls.

There are 20,000 talibés in Saint Louis alone, of whom about 15,000 are forced to

beg every day. If they do not meet their daily quota of money or if they do not

learn their lesson, they are subjected to corporal punishment and mistreatment.

Every day dozens try to escape their abusers, who sometimes lock them up or chain

them in shackles to prevent it.

At Maison de la Gare, Omar is woken up after having spent his first night indoors

in the last week. Modou enters the room and helps him dress in new clothes. On the

outside he looks like any other child, but the shadow of fear and sadness is still

there.  Maison de la Gare's social worker Thiéck Aw interviews him. She wants to

know why he ran away from the daara; a decision must be made.

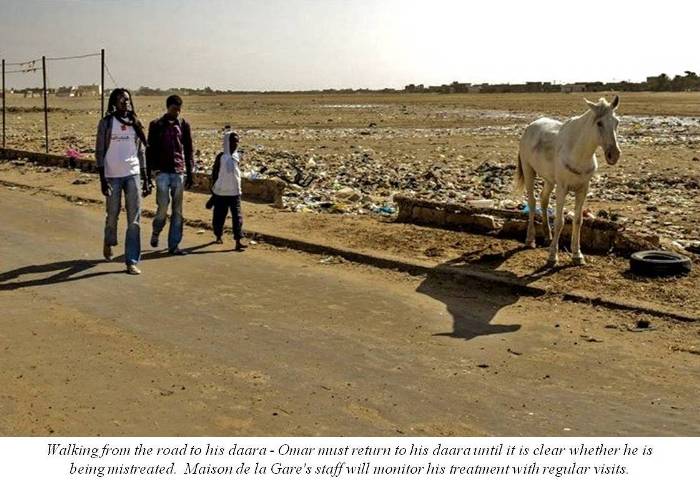

"We cannot leave him in the street," Modou says, "and if we take him

to his village, he will probably be

back here in three days. In this case, we see no evidence of corporal punishment

or physical ill-treatment. We think it is best to return him to his marabout and

then to follow the case to prevent it from happening again. It is not good for him

to continue at the bus station. Bad things happen there."

Maison de la Gare's social worker Thiéck Aw interviews him. She wants to

know why he ran away from the daara; a decision must be made.

"We cannot leave him in the street," Modou says, "and if we take him

to his village, he will probably be

back here in three days. In this case, we see no evidence of corporal punishment

or physical ill-treatment. We think it is best to return him to his marabout and

then to follow the case to prevent it from happening again. It is not good for him

to continue at the bus station. Bad things happen there."

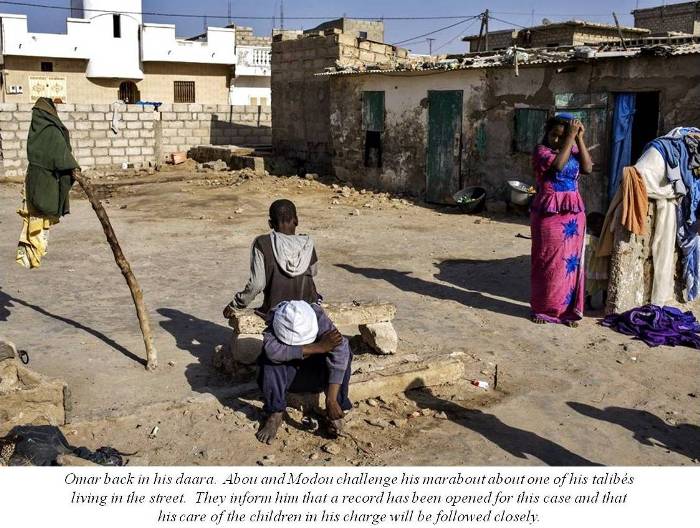

Back at Omar's daara, in the Pikine area of Saint Louis, his marabout Thierno

Sadibou takes charge of him. "We do not hit the children," he says. Samba and

Modou talk with him and warn him that they will visit every week, and that if

they see any sign of violence, he will be denounced. In recent years, Maison de

la Gare's team has managed to close seven daaras that did not meet minimum

standards, and their efforts have led to four marabouts being condemned to prison.

Some resist, but most collaborate.

________

Our sincere thanks to Alfredo Cáliz for the dramatic photographs illustrating this report.