News from Maison de la Gare

A Travesty against Humanity

Tweeter

A world that MUST change

“My name is Sokhna. I live in the village. I am 11 years old. I am a student going to school and

I live with my mother, my father and my sister. I am the first one in my family to go to school. My sister

married very young. In my village, parents give the girls in marriage when they are 12 years old. I am

becoming afraid that I will be forced to be married and not allowed to continue going to school.”

... name and details

changed to protect her identity

I have been reeling since I opened the envelope our friend Cheikh Diallo handed us, stuffed full of

written testimonies  of young girls, with their photos. Children testifying about their forced early

marriages, and their fear of being forced to marry far too young and forced to end their education and

dashing their hopes for the future. It is too much.

of young girls, with their photos. Children testifying about their forced early

marriages, and their fear of being forced to marry far too young and forced to end their education and

dashing their hopes for the future. It is too much.

Okay … I was not ready. It is now the next day. I am trying again.

Where do I begin?

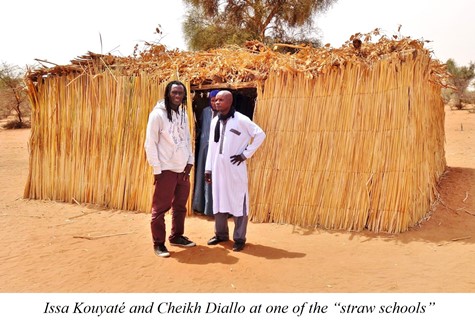

Several years ago, our friend Cheikh let us know he was trying to build a school in his village. He said

he was inspired by watching us year after year helping Maison de la Gare help the talibés. Many of the

begging talibé children in Saint Louis come from his village and region, Mbaye Aw. There were no schools

there. So, parents felt their only hope of education for their children at all was to send their sons to

daaras in the cities to learn the Quran. Building a school can change things, he thought. And he started

saving from his long days working as a street-corner cobbler.

When we found out about it, we started helping him. The first school was built. Then, this became a

Maison de la Gare, program, a way to keep the boys in their home villages so they would not become begging

talibés in the big cities. And a way to rescue boys from the region who were already begging on the

streets. More years of saving, and more schools were built.

When we visited several years ago, we saw the schools in action, met the talibés who had returned from

forced begging on the streets, and met the girls who were attending school for the first time ever because

now that is a possibility for them.

This is our report on that first visit. We gained a much better

understanding during that visit of the extent to which sending boys away to become talibés distorts life

for those left behind.  Many young girls see no alternative for their lives except to be married to an

older man, often as a second or third wife. The boys rarely return after many years living in the big

cities, so the girls and their families see few other options for them.

Many young girls see no alternative for their lives except to be married to an

older man, often as a second or third wife. The boys rarely return after many years living in the big

cities, so the girls and their families see few other options for them.

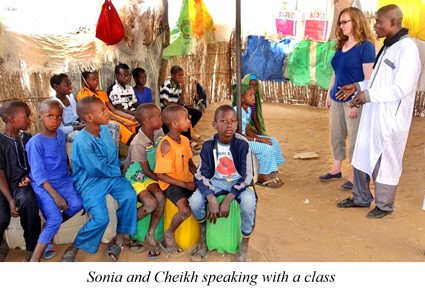

During the year 2022, 204 boys and 131 girls attended regular classes in the six schools established under

this project in the Mbaye Aw region. Three teachers and two volunteers teach the children. Many of the

boys were previously begging talibés in Saint Louis and elsewhere and had returned home for school.

This year, 65 students from the Mbaye Aw schools are in the town of Dahra Djolof writing their exams at

various levels, 34 boys and 31 girls. Twelve of these boys used to be forced-begging talibés. This is

an incredible achievement. Almost an impossible one! Hundreds of children, including girls,

are being educated.

But, of course, each success opens another pandora’s box, and then leads to much more to do.

We now understand that the talibé system likely contributes to the practice of early forced marriage

and polygamy. When boys disappear from their villages at an early age and rarely return, and there are

no schools, marrying the girls left behind to older men, multiple girls to each man, may seem to be a

logical and perhaps even the only choice to the villagers. Our experience in Mbaye Aw suggests that

building schools in the villages not only makes it possible for talibés to return home. It also makes

it possible for the girls to begin to study, to discover, to learn about human rights. With time, there

will be boys their age to marry in the villages, in equal numbers once more. And this can reduce

pressures for forced early polygamous marriages.

Schools in the villages could be the key to ending two forms of modern slavery, for boys and for girls.

Freeing boys from slavery as forced-begging talibés, and girls

from forced premature marriage

to polygamous husbands.

from forced premature marriage

to polygamous husbands.

We are now in the time between awareness and opportunity, and the change to come. This is surely the

hardest time. The traditions of child forced marriage remain. But the reasons for it do not, thanks

to the schools built in these villages. I have no doubt that change will come. But, in the meantime

the testimonies in the envelope that Cheikh gave us, and the pictures of the hopeful, newly educated

young faces looking as if into my eyes, what of them?

“My name is Aïssa. I live in the village and I am 12 years old. I am a student at the school.

I live with my father and mother and my brothers. My father wants to give me in marriage but I

refused, as I want to continue with my studies. I have even spoken with the old man he wants to

give me to and explained I want to study at school. It will not be easy, but I am determined to fight

to continue to study. I am also determined to fight against forced child marriage. But I can’t do it alone.”

... name and details changed to protect her identity