News from Maison de la Gare

Into the Bush, in Search of an Education

Tweeter

Cheikh Diallo’s vision lights a new path for village children at risk of becoming talibés (as told by Sonia LeRoy and Rod LeRoy)

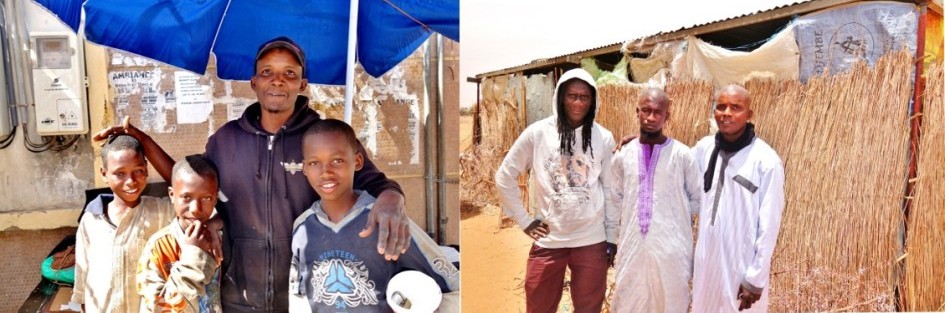

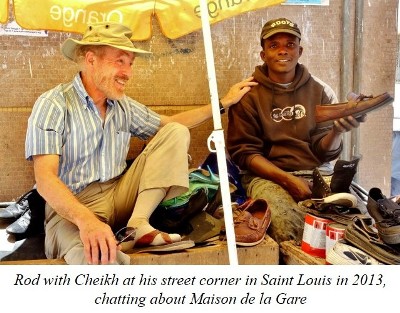

For many years, we have known a local

cobbler in Saint Louis who has become a friend and an inspiration. Cheikh Diallo, in

turn, claims that we have inspired him. As he learned of and watched our work as

volunteers and partners with Maison de la Gare, he began to

save his earnings toward

building a primary school and supporting teachers in his home village in the region of

Mbaye Aw. After many discussions (while repairing shoes) about how education can

provide hope, and change everything for a child such as a forced begging talibé,

Cheikh had become a believer.

save his earnings toward

building a primary school and supporting teachers in his home village in the region of

Mbaye Aw. After many discussions (while repairing shoes) about how education can

provide hope, and change everything for a child such as a forced begging talibé,

Cheikh had become a believer.

His idea is simple. If education is accessible locally, families will not be tempted

to send their boys to cities to become talibés. Impressed with Cheikh's dedication to

providing opportunity, we contributed regularly to his dream and, eventually, the first

school was built.

When the ongoing challenge of funding teachers proved beyond

Cheikh's means, we introduced him to Issa Kouyaté to ally this unique project with

Maison de la Gare. Cheikh invited us to visit Mbaye Aw to see the project ourselves,

an invitation that we accepted enthusiastically.

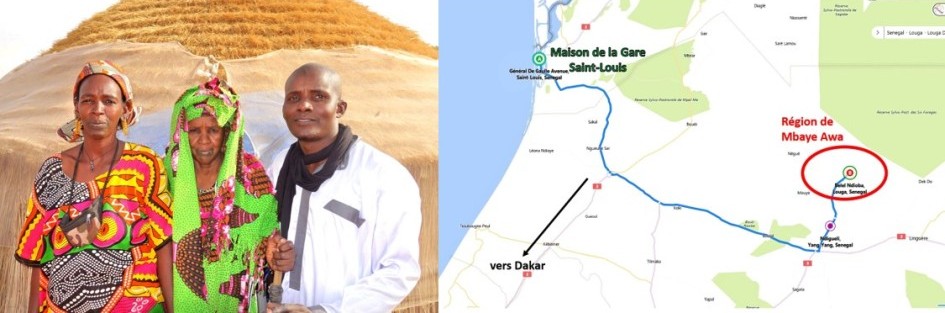

We left Saint Louis for the district of Mbaye Aw at 9 a.m. However, it soon became

clear that we should have left much earlier. One hour down the-well paved highway to

Louga, then a left turn inland to the town of Dahra Djoloff, over 100 km on a very

badly potholed road.  Although we drove carefully so as not to join the other flat-tired

vehicles along our route, the hours surely amounted to far more distance than was

estimated. Along the way were herds of dromedaries and as many donkeys and goats as

holes in the road.

Although we drove carefully so as not to join the other flat-tired

vehicles along our route, the hours surely amounted to far more distance than was

estimated. Along the way were herds of dromedaries and as many donkeys and goats as

holes in the road.

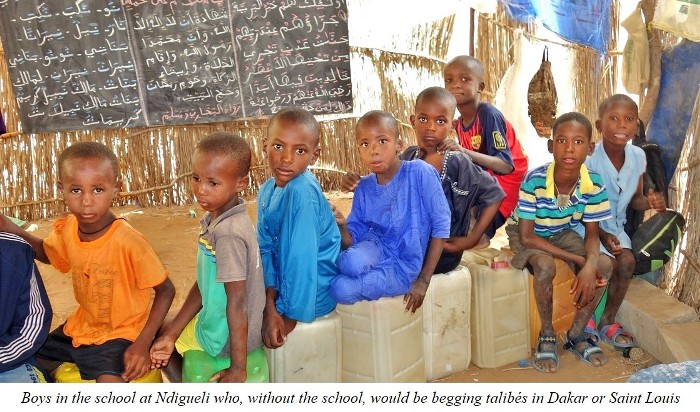

Not long after Darha Djoloff, the "paved" road ended. And, not too long after that, we

cut off the main road onto a dirt track leading through the sandy scrub. This part of

the country is referred to as the bush. The first school we arrived at was in the

village of Ndigueli.  It had 28 students, including 4 girls. Girls marry as young as

12 or 13 here, so it is rare for parents to educate them. Cheikh and his

collaborators are making a major effort to convince parents to send their girls to

school, and to help to obtain birth certificates so these kids can get national

identity cards and thus, someday, have the option of continuing past primary school;

this is not possible without papers.

It had 28 students, including 4 girls. Girls marry as young as

12 or 13 here, so it is rare for parents to educate them. Cheikh and his

collaborators are making a major effort to convince parents to send their girls to

school, and to help to obtain birth certificates so these kids can get national

identity cards and thus, someday, have the option of continuing past primary school;

this is not possible without papers.

About an hour past Ndigueli we came to a water well. This well serves an area of many

square kilometers. Most villages do not have their own water source, so the women walk or

drive donkey carts for great distances to collect water for their villages. Two women

at the well were collecting water in traditional containers ... old inner tubes ...

with babies strapped to their backs; they had travelled six kilometers to get

to the well. Collecting water can be nearly a full-time job for the women of villages

in the bush.

water can be nearly a full-time job for the women of villages

in the bush.

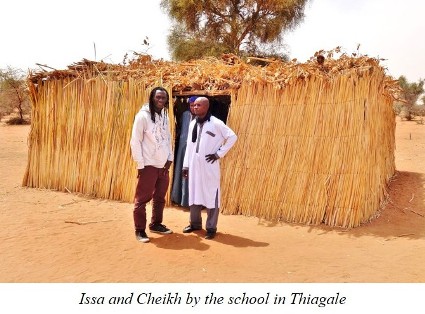

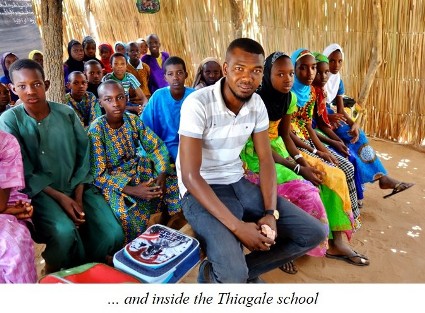

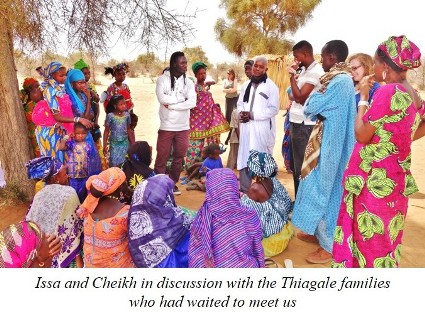

Kids were still in class at the second school we visited, at the village of Thiagale.

Like the first school in Ndigueli, the building was constructed of cut wooden poles

and straw walls. These buildings apparently suffer significant damage during the

rainy season and are then repaired or rebuilt. Or not, depending on the means of the

villagers at the time. At this school a welcoming committee of all the village

mothers awaited us. We were a tremendous curiosity to this very isolated community.

Of the 31 students in this school, 12 are girls. And only one child in the school

has papers. Many of the students in the school walk for hours to get here. They

know education is important, possibly their only hope for something better.

Life in these remote villages is hard. Food is more abundant

after the rainy season but, at this time of

the year at the  start of the summer, it is much scarcer. The distance to travel to obtain water contributes to

life's many challenges here. When there is no education available, what else is

there but to marry young, start a family and continue the cycle. Many boys are sent

to daaras in the cities to be talibés, although this practice is diminishing thanks

to the schools that Cheikh has founded. Cheikh explained that education will help

these kids to expect and to actively seek better for themselves. Education will

encourage change to happen here.

start of the summer, it is much scarcer. The distance to travel to obtain water contributes to

life's many challenges here. When there is no education available, what else is

there but to marry young, start a family and continue the cycle. Many boys are sent

to daaras in the cities to be talibés, although this practice is diminishing thanks

to the schools that Cheikh has founded. Cheikh explained that education will help

these kids to expect and to actively seek better for themselves. Education will

encourage change to happen here.

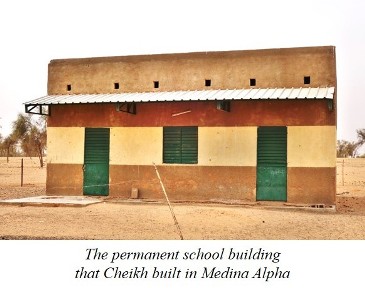

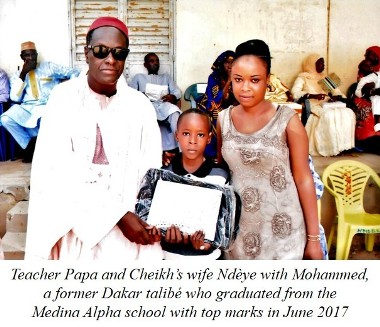

Another half hour journey and a few wrong turns later we arrived at the village of

Medina Alpha. There are 5 boys and 23 girls at this school. This is the first of the

four schools to be constructed as a solid-walled building that can withstand

the elements, and the leaders and parents of this village have embraced the hope

offered by education. It is run as a modern school and all

classes are taught in

French. All the children here have papers. Cheikh and the teachers are working to

identify and bring home the boys from this village from the cities where they have

been sent to be begging talibés, a realistic hope now that true education is

available locally. Many boys have come home.

classes are taught in

French. All the children here have papers. Cheikh and the teachers are working to

identify and bring home the boys from this village from the cities where they have

been sent to be begging talibés, a realistic hope now that true education is

available locally. Many boys have come home.

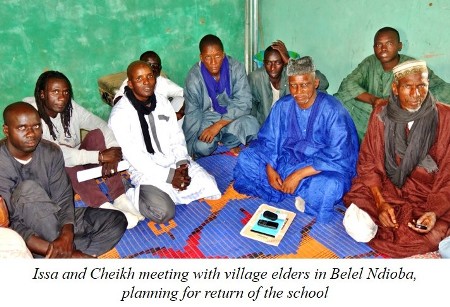

The last school site we visited, at Belel Ndioba, sadly no longer exists. A straw-walled

school like two of the others, it was soon dismantled when the teacher left;

it did not take long for the abandoned building to be reclaimed by the elements and

needy neighbors. This school required a fee of about $3 per month per child and,

when a critical mass of parents could no longer pay, the teacher stopped coming.

43 children have had their education suspended, 19 girls and 24 boys. The villagers

here hold out hope that Maison de la Gare can make something happen

for their children.

for their children.

We finished the tour with a visit to our friend Cheikh’s home village, Wouro Seno. As

usual, there is no water source here and the women walk two kilometers each way daily

to collect water. By the time we had finished a feast in honor of our visit and had met

all Cheikh's family, we knew we would not make it back to Saint Louis before dark. But,

we did reach the "paved" road just before the sun set.

As we climbed out of the vehicle after 10 p.m., we all reflected on our own good fortune

to have such ready access to water and the other necessities of life and, above all, to

education and thus to opportunity. And we marveled at Cheikh’s courage and vision in

giving everything he has to make possible a promising future for the boys and girls of

his village and others like it.

_________________

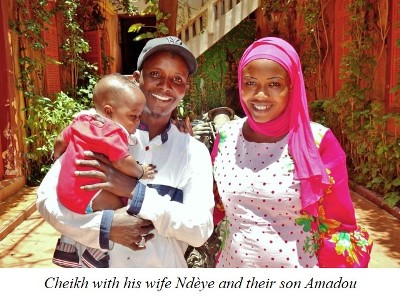

p.s. There is an incredible human aspect of this story that we must share with you.

When Cheikh told the village chief of Medina Alpha of his vision to build the school,

the chief was completely supportive. In fact he said that, if the school were really

built, he would give his daughter Ndèye to Cheikh in marriage. The school was built,

graduating its first students in 2017, and Cheikh and Ndèye were married that same year.

They are very happy, and their son Amadou was born in January of this year.

the village chief of Medina Alpha of his vision to build the school,

the chief was completely supportive. In fact he said that, if the school were really

built, he would give his daughter Ndèye to Cheikh in marriage. The school was built,

graduating its first students in 2017, and Cheikh and Ndèye were married that same year.

They are very happy, and their son Amadou was born in January of this year.