News from Maison de la Gare

I am Arouna Kandé

Tweeter

A talibé shares his experience of life, and the role played by Maison de la Gare

My name is Arouna Kandé. I am a

talibé and Administrative Assistant at Maison de la Gare. I grew up in Kolda in

Casamance in the south of Senegal. I was sent to a daara in Saint Louis in 2006 when

I was nine years old, to pursue my study of the Koran. I left behind my parents and

three younger sisters, who are always in my thoughts. And, while I've been in Saint

Louis, both my father and mother died and I became an orphan.

study of the Koran. I left behind my parents and

three younger sisters, who are always in my thoughts. And, while I've been in Saint

Louis, both my father and mother died and I became an orphan.

When I arrived in Saint Louis, I saw children all around the city with begging bowls

in hand, wandering barefoot with torn and filthy clothes and having no way to wash or

get medical treatment. I thought in my head: "What kind of a world is this? What's

the point? Why be alive when there is no possibility to be yourself?"

I was sad from sunrise to sunset, wandering with my hands in my pants pockets. At

such moments, my thoughts always turned to my family. Ah!!! With my family I could

have discussed things; I would have been able to express my opinions. But, in the

marabouts' world I was, like all the other children, a slave.

After three years of living this ordeal, I came upon an association called Maison de

la Gare. I was introduced by one of my comrades who had been going to Maison de la

Gare's center every day.

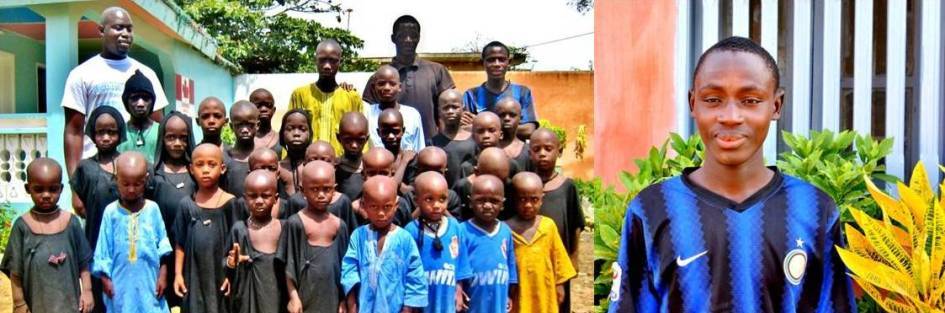

Maison de la Gare is a non-profit organization, non-political and secular, that was

founded in 2007 by a group of Senegalese driven by a desire to improve the living

conditions of talibé children in their country, Senegal. Maison de la Gare's

objective is to help the talibés to integrate into Senegalese society, both socially

and professionally, by providing them with access to education, sports and artistic

activities and apprenticeship opportunities.

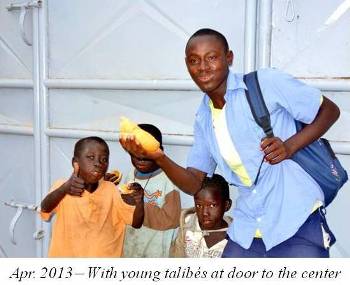

From my early days at the center, I saw many children in the courtyard. Others

were in the classrooms, in the infirmary, in the library or showering. It was

unimaginable for me to see all the talibés at home in the center as though they

were with their families. After a week, I started attending basic literacy classes

with Bouri Cherif Mbodj, one of the center's French teachers. I would go to the

center in the mornings to wash and sometimes to get treatment for ailments or

injuries. And I would return every evening on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays

for Math, French, History and Geography classes. On Thursdays and Fridays, we

organized soccer games with other children from around the city of Saint Louis.

Sports make a great

in the infirmary, in the library or showering. It was

unimaginable for me to see all the talibés at home in the center as though they

were with their families. After a week, I started attending basic literacy classes

with Bouri Cherif Mbodj, one of the center's French teachers. I would go to the

center in the mornings to wash and sometimes to get treatment for ailments or

injuries. And I would return every evening on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays

for Math, French, History and Geography classes. On Thursdays and Fridays, we

organized soccer games with other children from around the city of Saint Louis.

Sports make a great  contribution to children's development, helping them to better

prepare their future.

contribution to children's development, helping them to better

prepare their future.

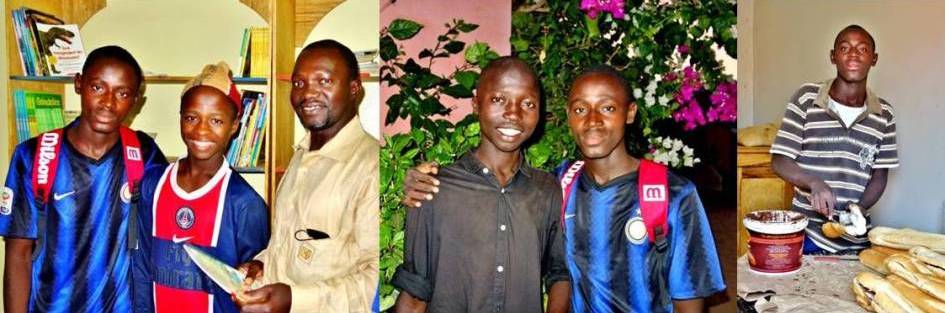

I mastered basic French grammar in just three years. Finally I announced to Issa

Kouyaté, Maison de la Gare's president, that I wanted to go to school. He asked

me "Arouna! Are you afraid to speak out in class?" I said "No". Then he asked

me "Arouna! Are you afraid to play with your classmates?" Again, I answered

"No". He enrolled me in a public institution named CEM Amadou Fara Mbodj, a

school located in the north of Saint Louis.

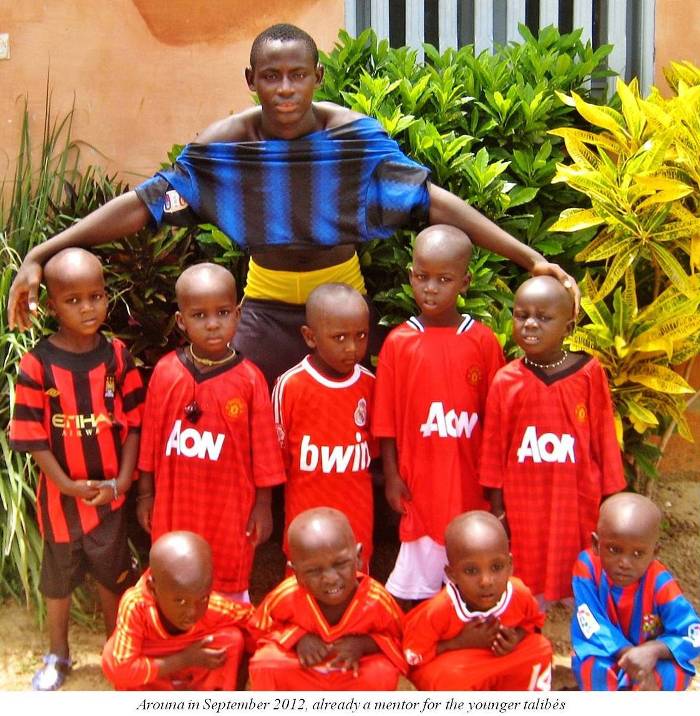

By the age of only sixteen, I had gained enough knowledge to become a leader and

an example for the other talibés. I devoted myself to my studies and often missed

the football games or other activities as a result. At times, I studied and did

my homework in my daara until midnight by the light of the moon. Despite my

experience of the street, no one forced me to beg. I always devoted time to

obtaining a small quota of money for my marabout. To do this, I sold fish in the

local market that I had found on the banks of the Senegal River, discarded by

fishermen. Still, I always had time to look after the young talibés. I was also

available to help with the many chores required for the smooth running of the center.

or other activities as a result. At times, I studied and did

my homework in my daara until midnight by the light of the moon. Despite my

experience of the street, no one forced me to beg. I always devoted time to

obtaining a small quota of money for my marabout. To do this, I sold fish in the

local market that I had found on the banks of the Senegal River, discarded by

fishermen. Still, I always had time to look after the young talibés. I was also

available to help with the many chores required for the smooth running of the center.

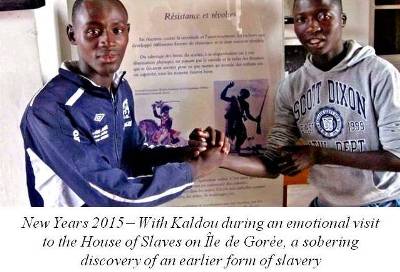

Even beyond questions about life for children in the daaras, I asked myself about

their lives after  the daara: what can they do in life if they don't speak French

(the official language in Senegal) and have no professional skills? The best of

them become themselves marabouts or Arabic teachers, but what about the rest?

Throughout my entire childhood, the age when a child learns about life in society,

I was marginalized from everything ... because of my smell, my clothing and the

fears of the other children's parents. I also lacked any of the skills necessary

to find a job, even a most rudimentary one!

the daara: what can they do in life if they don't speak French

(the official language in Senegal) and have no professional skills? The best of

them become themselves marabouts or Arabic teachers, but what about the rest?

Throughout my entire childhood, the age when a child learns about life in society,

I was marginalized from everything ... because of my smell, my clothing and the

fears of the other children's parents. I also lacked any of the skills necessary

to find a job, even a most rudimentary one!

People say that today's youth are the society of tomorrow. What type of society can

we build if our children are treated like this? Let's not delude ourselves; a Muslim

education is fine but we must also have technical skills. The truth is that if I find

myself as an adult without skills or employment, I will be lost to society and will

swell the ranks of those outside the law.

skills or employment, I will be lost to society and will

swell the ranks of those outside the law.

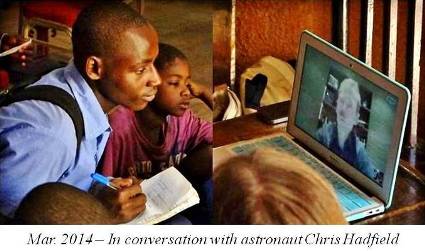

Maison de la Gare has become my family. I am also encouraged by my contacts with my

correspondents in Canada via the Internet, and by volunteers at Maison de la Gare who

know my qualities and my potential.

Myself and so many other children like me, we are the future of Senegal.