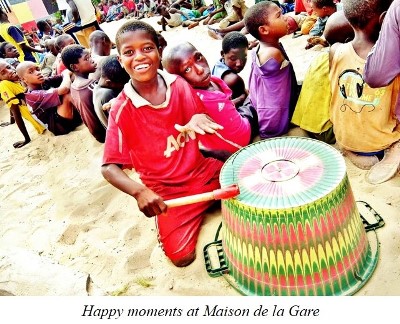

News from Maison de la Gare

Who are the Talibés? Why Do They Beg?

Tweeter

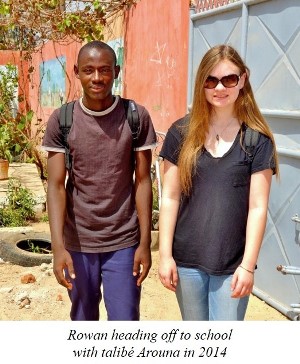

Rowan Hughes shares her understanding of this complex issue, after eight years involved with Maison de la Gare and the talibé children

Across the globe and throughout history, certain vulnerable groups have been unfairly exploited.

And their exploiters in positions of power have taken advantage of this and the

law has turned

a blind eye.

law has turned

a blind eye.

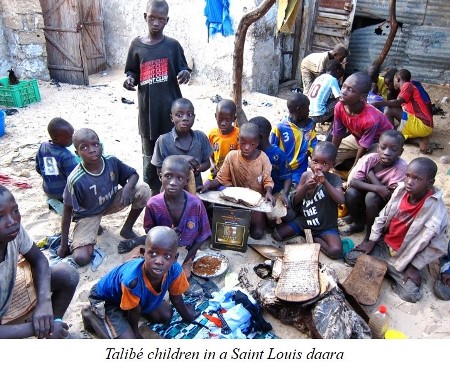

The Senegalese talibé system has its roots in the 14th century but it has evolved dramatically

since about the 1960s, from a respected system of religious education and character building

into a fraught system of exploitation. Today, predominantly rural families entrust their sons

to urban-based Islamic teachers known as marabouts. However, instead of receiving the

anticipated Islamic education, tens of thousands of these “talibé” children typically

experience conditions of deprivation, extreme corporal punishment and being forced to beg for

daily quotas of money as well as their own food for 8 to 10 hours a day. The United Nations

considers the talibé system today to be a form of modern slavery.

Marabouts

Marabouts are the principal perpetrators of talibé abuses. Some of them have recruitment

systems that extend to villages in neighboring countries, escalating the talibé system to

international child trafficking. Many marabouts force their talibés to beg for their own

personal enrichment, but it was not always this way.

The talibé system originated as one of the first formal systems of education in West Africa,

based on a trust relationship in which marabouts were responsible to and supported by local

populations. All talibés, whatever their origin or family wealth, practiced a moderate

amount of begging, not to enrich the marabout but rather to teach them humility. Daaras

were in the community or a nearby village where their proximity to home allowed talibés

and their families to remain in close contact. Families made small financial contributions

to the daara and children regularly returned home to eat, wash, clean their clothes, and

to spend time with their families.

Just over half a century ago when drought worsened in Senegal, severe impoverishment

resulted in rural villages. This induced many marabouts to move their daaras to

relatively more prosperous cities. Rising poverty in the villages

made it difficult for

families to continue to financially support the marabouts and, after the transition to

cities, parents ceased to play an active role in supporting their sons. This migration

of daaras from rural villages has expanded to become thousands of daaras in cities across

Senegal today, where marabouts use forced begging by the children as their primary means

of support.

made it difficult for

families to continue to financially support the marabouts and, after the transition to

cities, parents ceased to play an active role in supporting their sons. This migration

of daaras from rural villages has expanded to become thousands of daaras in cities across

Senegal today, where marabouts use forced begging by the children as their primary means

of support.

Civil Society

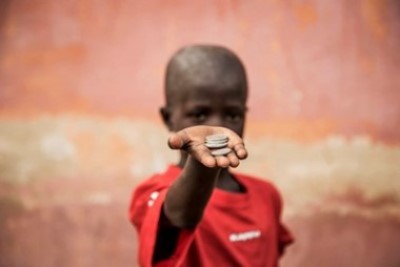

Civil society’s role is key to understanding why forced begging persists. Senegalese

citizens contribute to condemning the talibé system to be a classic poverty trap. They

coexist daily with the talibés and are often indifferent to their distress. Even worse,

most citizens donate generously to talibé begging bowls but, unfortunately for the talibés,

this generosity only feeds the system which exploits them.

Senegalese support of the talibé system is deeply rooted in the country’s religious and

cultural history. Koranic schools have been a key symbol of Muslim identity in West

Africa since the 14th century and marabouts, as the leaders of these schools, have an

unusually strong influence. An emphasis on rote learning and Muslim duty reinforces

individuals giving to the talibés less out of compassion than from societal expectations,

without examining too closely who or what they are really giving to. Some of the abuses

experienced by talibés in daaras are not considered as offensive to Senegalese society

as they may be to international organizations that advocate for children’s rights.

Further, some of the most serious abuses happen out of the public eye and are thus

easy to overlook.

Civil society is a critical lever of potential change; if individuals stopped giving

to the talibés, the system would quickly come to an end.

Other Actors

The state has had a dual role in perpetuating the talibé system: not enforcing

forced-begging laws, and indirectly legitimizing the begging daara system as an

educational system. Senegal’s penal code long ago criminalized forced child begging.

However, only a handful of cases have been prosecuted in a landscape of thousands of

daaras where children are forced to beg. This governmental laxity reflects the

political influence of the marabouts, the overwhelming scope of the problem, and

scarce resources. Despite political rhetoric, enforcement of forced begging laws

remains elusive.

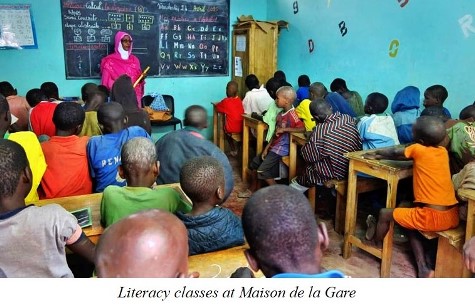

There are many in Senegalese society who call for change. Some civil society

organizations, Maison de la Gare being a leader among them, work to educate people

about the severity of the conditions faced by talibés. These organizations have

had an important impact in improving the children’s living conditions and prospects

for the future, and they advocate tirelessly for an end to the talibé begging system.

The international community is another actor that could play a stronger role in

encouraging the state to change its behavior with respect to the talibé system.

For example, by pressuring government leaders with respect to human rights for

children and supporting the civil society organizations that work to end forced

begging, such as Maison de la Gare.

Families of talibé children are important actors as well. If parents stopped sending

their children to be talibés, the system would fall apart. However, the importance

of Islamic education and the influence of marabouts are particularly powerful with

rural and often uneducated parents. Furthermore, when there are no local schools,

families have very few options if they want their children to receive an education,

and the promise of an Islamic education in an urban daara is often the only option

available. Finally, some parents are simply unaware of the severity of the conditions

of deprivation, forced begging and abuse experienced by their children.

The unintended consequences of parents sending their boys from rural villages to the

cities are far reaching and severe for society, not just for

the talibés. A visitor

to many rural villages in Senegal that have sent boys to be talibés in the cities will

observe a dramatically disproportionate number of girls. It is common in these

villages for girls to marry as young as 13 or 14 to older men who already have other

wives. The lack of schools in rural villages not only encourages the talibé system

but promotes polygamy, child marriage and female illiteracy.

the talibés. A visitor

to many rural villages in Senegal that have sent boys to be talibés in the cities will

observe a dramatically disproportionate number of girls. It is common in these

villages for girls to marry as young as 13 or 14 to older men who already have other

wives. The lack of schools in rural villages not only encourages the talibé system

but promotes polygamy, child marriage and female illiteracy.

Another distressing unintended consequence is the inability of talibés to become

productive members of Senegalese society. Issa Kouyaté, Maison de la Gare’s founder

and president, has long understood this. His primary objective for Maison de la Gare,

apart from ultimately ending forced begging in Senegal, is to provide means for talibé

youth to learn to become successful and productive members of society.

What can we do?

The trap that talibé children experience is a result of many complex factors.

Marabouts, civil society, the talibés’ families, government, and the international

community all are actors who play a role, either through action, or through lack of

action that perpetuates the horrors of the talibé system. Influencing parents to

keep their children at home by building schools in rural areas and encouraging daaras

to return to their rural roots have significant potential, as does pressure and

targeted aid from the international community.

at home by building schools in rural areas and encouraging daaras

to return to their rural roots have significant potential, as does pressure and

targeted aid from the international community.

We can also work to establish an effect collaboration between parents, marabouts,

talibé children, civil society, and organizations like Maison de la Gare. Direct

communication between all these stakeholders is essential if we are to achieve true

protection for the children. Together, we can dismantle the illegal practices of

the exploiters. Only such a collaboration can bring about real change for these

thousands of abused children.

Importantly for our readers, donations made through grassroots organizations such

as Maison de la Gare offer more than just hope. They offer the potential

for real change.

__________

Rowan Hughes first visited Maison de la Gare in 2012 at the age of 14. Since

that time, she has made nine more trips to Saint Louis as a volunteer and is now

completing a degree in International Development at the University of Guelph

in Canada.